The Three Faces of Garry Knox Bennett (2001)

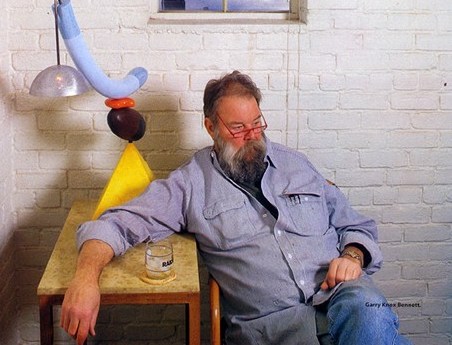

Photograph of Gary Knox Bennett in his Oakland loft by Joe Samberg, 2001.

The Three Faces of Garry Knox Bennett (2001)

by Abby Wasserman

Pectus est quod disertos facit

It is the heart that makes men eloquent.

--Quintilian

Arriving for a luncheon interview recently at Garry Knox Bennett's Oakland loft, I am welcomed with a big hug by Geraldo Bennucci. "Ambrose is making lunch," he says, referring to Ambrose Pillphister, the painter, "and Garry's debating a fine point with a band saw. Vino?"

Delighted that I am going to meet everyone when I'd only expected Garry, I accept a glass. It's rich and smooth, with a manzanita flavor and complex afterthoughts of cherries and rutabaga. "This is no vino ordinario," I say admiringly to Bennucci, who inclines his head modestly.

"Made in Oakland," he affirms, gesturing toward the back deck. Through the glass I can see, among the lemon trees, a miniature vineyard in planter boxes.

"Garry crushes the grapes," Bennucci says, laugh lines dimpling. "He's got the biggest feet." Geraldo is funny in a sophisticated, Italianate way. He designs jewelry and lighthearted lamps that Oakland Museum curator Suzanne Baizerman calls "pure play."

We enter the kitchen through a pair of tall, intricate screen-like doors that remind me of inlaid waffles. One wall is industrial red brick, another mostly windows, a third boasts a series of Garry's calligraphic acid etchings on steel plates using a resist technique he developed.

Ambrose Pillphister turns from the stove to greet me. Part of the Bennett household since the 1960s, he's the intellectual of the family--serious, focused and a bit shy. A reader of Nietzsche and Kant, he thinks deeply about time, light and the maximization of storage space. His moniker is a combination of Ambrose Bierce, Garry's favorite humorist, and Heine Schupister, a sailor Garry heard of during his own extended sailing phase.

It was Ambrose's idea to create secret messages and designs inside Garry's furniture, but in a strict division of credit, Ambrose signs his name only on the paintings he turns out, which are few but choice. After the Oakland fire in 1991 he painted an empathetic series of small works on squares of gessoed wood, showing flames either engulfing or passing over houses. They're like icons or invocations to the fire god. He saw the blaze from a plane coming in for a night landing at the San Francisco airport.

Garry hasn't come upstairs and the food's ready, so Ambrose insists we sit down. Many painters have a penchant for the culinary arts and Pillphister is no exception. Garry, Geraldo and Ambrose share cooking duties, but Ambrose is the acknowledged master. The tiger prawns and pea pods with caper sauce are followed by rigatoni with tomato sauce. Sun streams through the windows, the wine smooths out the wrinkles of the morning, the conversation is mellow. I am filled with a sense of well-being.

Suddenly, a downstairs doors slams, feet sound heavily on the steps and a voice booms, "Hey, what the hell's going on here? Eating without me? How dare you!" Garry Knox Bennett enters the kitchen, six-foot-nine in his welding boots, dressed in jeans and a starched work shirt. His eyebrows and fine grey beard wiggle in righteous indignation.

"Oh, calm the f--- down," Geraldo says soothingly, pulling out a chair.

The furniture maker and his alter egos, Bennucci and Pillphister, share the loft on Fourth Street in Oakland with their wife Sylvia. Although the Bennetts also have a beautiful house in Alameda, Garry prefers their Oakland digs because the studio downstairs is where he spends most of his waking life. Alameda is his birthplace (and that of his grandmother, mother, father and daughter), but he's an Oakland guy. His retrospective this year at the Oakland Museum of California, and the book that accompanied it, are called Made in Oakland: The Furniture of Garry Knox Bennett.

Oakland and furniture-making are states of mind for Garry, as serious as the Raiders, the estuary, the port, and working men's bars. Not art to adorn walls. Not Frisco preciousness. This is stuff people use, honest, outspoken, inventive and playful as the maker himself.

Oakland Fire 1 by Garry Knox Bennett

The retiring Ambrose Pillphister and the vivacious Geraldo Bennucci give Garry the freedom to do what he wants in the all the media in which he likes to work. "He tries consciously to keep influences, even his own, from becoming too invasive," explains Sylvia Bennett. "By naming the different avenues he takes, he can separate them, keep them clean. When he's painting, he paints. When he's making furniture, the other two are quiet.

"There is some overlap. You'll see a lot of the painting from his furniture appear in his jewelry, but the painting in the furniture tends to be hidden in drawers or unseen places, almost secret. It is a bit multi-personality, but his voice doesn't change."

"Garry says he's not an artist," says curator Baizerman, who organized the exhibition. "He prefers to be called a furniture maker. Art is dead-serious for Garry. Maybe he couldn't have so much fun with wood if it had to be art.

"If you're Garry Knox Bennett you can't doodle around with jewelry, because you're a furniture maker. So Geraldo does the jewelry. Ambrose is the artist; he does what he pleases. I'm sure Ambrose has no trouble being an artist. Garry keeps all the plates spinning that way."

Garry Knox Bennett was born in 1934. Both grandfathers and his father were sea captains, and he had his own little boat as a child. His penmanship at the age of nine was so pretty that his teacher told him she thought he would be an artist.

After an academically desultory high school career he worked in mailrooms, bars, automotive plants and warehouses, but also began to paint seriously. In 1960 he made two choices that changed his life: he entered the California College of Arts and Crafts and wed Sylvia Mangum, a high school friend, in a Gothic chapel at the back of an old estate, which they rented from Esther and Fenner Fuller, art patrons who helped create the Oakland Museum.

At CCAC Garry studied sculpture and painting. He taught himself to weld and made his first series of figurative steel sculpture. He was among those responsible for the first driftwood beach sculptures on the Emeryville mud flats. His work was selling, but economically things were tough. In 1962 he accepted an invitation to work on his stepfather's rice farm in the Sacramento Valley. He and Sylvia moved to an A-frame Garry built for them on the property, his first major experience in woodworking. Joshua and Aaron, the Bennetts' two sons, were born during the five years in the valley.

"We lived in abject poverty," Garry says. "Sylvia said you know something's wrong when the Sears catalog fashions start to look good. I'd work on the spring planting and the fall harvest and earn only $800 a year. We lived on jack rabbit, pheasant and duck we got hunting. We had a neighbor saving bacon grease for us; Sylvia made great cornbread with bacon grease and cornmeal. I once bought her eight pounds of butter for her birthday."

He continued to paint and sculpt and made friends with artists who were around the University of California at Davis--Mel Ramos, Wayne Thiebaud, Robert Arneson, Jack Ogden. In 1962 he decided to relegate his painting to an alter ego, Ambrose Pillphister.

The hardscrabble life on the farm came to a halt when Garry complained about something one day and his stepfather said rashly, "If you don't like it here, leave." He borrowed $500 from his cousin to move the family back to Alameda, where their daughter Jessica was born. During the next few years Garry set up a metal plating shop which is still operating. He made a series of clocks with decorative electroplated metal surfaces which he sold at Gump's in San Francisco, gradually building a successful business. He likes to say he was educated at the School of Hard Knox, and truth to tell, he learned most everything he knows by working it out himself.

Tablelamps by Garry Knox Bennett

In 1979, Garry was invited to participate in The Cutting Edge: New Works in Wood at Contemporary Artisans Gallery in San Francisco. For the show he created "Nail Cabinet," and it turned the woodworking community on its ear. Employing his now considerable skills as a craftsman, he built a tall cabinet of wood and glass, and right when he had it perfect, he pounded a 16-penny nail crudely into its pristine surface and smacked the wood a couple more times for good measure, leaving marks. When "Nail Cabinet" was reproduced on the back of the magazine Fine Woodworking, he was vilified by some as "the Philistine who did that horrible thing to that cabinet," but many others got the point: it's not the medium that makes something worth looking at, but the idea behind it.

"The nail was planned from the beginning," Sylvia says. "You can't believe the reverence that people gave wood. He wanted to see more design, creativity in the way people were working. Wood is a good vehicle but it's not the end--it's the beginning. He knew the furniture show would involve other furniture makers, and it would get their attention."

Besides being a great iconoclastic gesture, the nail was "a kind of punchline to a joke about the purity of art," writes Arthur C. Danto in the book Made in Oakland. "It was not a moment of discovery which required him to pound nails into future pieces. It was not the frenzied hammering of someone showing rage. It was, rather, a gesture of liberation, the sacrifice of modernism in the name of artistic freedom. It was a tremendous moment, and there was no need to repeat it."

The Bennetts' remodeled Oakland loft has big angular windows and skylights that suck in sun. The door frames are painted bright yellow, and Garry has built a sculptural pillar and floor-to-ceiling display cabinets to divide up the long living room. Ambrose and Sylvia chose the colors, and the broad and subtle humorous touches that abound are Garry's and Geraldo's, including the "wind directional device" on the deck which is made out of a missile cone.

Ambrose's Oakland fire paintings line the walls of the sitting room. The CD collection includes Geraldo's Italian operas ("I'm crazy about sopranos; I like the stabbing scenes"), Garry's Emmy Lou Harris albums, Ambrose's whaling shanties. There's a big TV set that Garry uses "to unplug his brain after working in the studio all day, or he'd never stop thinking about his work," Sylvia says. But Garry's relationship to television is uneasy. He has killed three TVs with a shotgun because of the garbage he says he was forced to watch.

Despite such memorable rages visited on inanimate objects, Garry is essentially a gentle person. "When I knew him really early on, he was a bouncer at the old Monkey Inns at San Jose and Oakland," Sylvia says. "It was really hard for him to be mean. He would just escort people out. He knew he could intimidate with his size so he didn't have to get physical."

He's a deeply loyal friend. "People have a sense of security being around Garry," says furniture maker Wendy Maruyama, a close friend. She remembers one evening seeing Garry and a group of children skipping down the sidewalk together.

Artist and metalworker Reynaldo Terrazas has known Garry since he was 19. They share a birthday, October 8th, and have worked together on many projects. "He does most of his

furniture--metal, wood--himself, but his biggest pieces in woods I transpose into metal. Garry's always a hands-on person. I know my abilities and skills but Garry, being the person he is, wants to be involved in what's done. I was working on his "Steel Trestle Table" and he was telling me how I should do this and that, and he realized what he was saying to me, and felt apologetic. He said, 'Aw, Jesus, I'd tell a brain surgeon what to do.'"

Jody Terrazas, an artist and Reynaldo's wife, recalls Garry's 60th birthday party, when the cake was brought in and 150 guests began to sing spontaneously, Happy birthday, f--- you, happy birthday, f--- you. . . . "The kids were flabbergasted to hear the adults singing this, but it was totally loving, and of course Garry just loved it."

Garry dominates our lunchtime conversation, keeping us off-balance, as he loves to do. He delights in being outrageous. He is alternately profane, whimsical and sweet as a bear in honey. He's also very funny, and it's too bad I can't print any of his jokes here. He dishes out insults with the dessert and grins when insulted back.

I muse that Geraldo's sophistication shows in the jewelry he designs, but Garry guffaws. "Aw, we wouldn't bother with that junk if I didn't get burned out making furniture," he says gruffly, ruffling Geraldo's beard, and Geraldo comes right back with "It's the jewelry that keeps you sane, you crazy German!" Ambrose smiles indulgently. It's just a little ribbing between alter egos.

Images from top:

- Photograph of Gary Knox Bennett in his Oakland loft by Joe Samberg, 2000.

- Oakland Fire #1 by Ambrose Pillphister (Garry Knox Bennett), 1993.

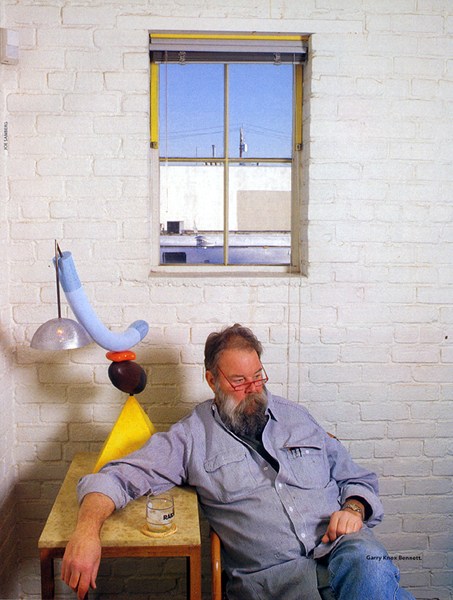

- Geraldo Bennucci (Garry Knox Bennett) with Tablelamps, 2000, photographed by Joe Samberg.

© 2000-2005 Abby Wasserman.

Originally published in The Museum of California magazine under the title The Three Faces of Geraldo Bennucci.