The Desert Years of Noah Purifoy (1998)

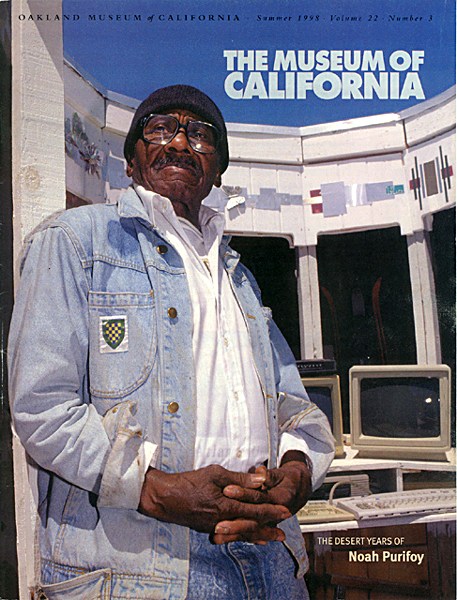

Cover of The Museum of California magazine, Summer 1998. Noah Purifoy photographed by Joe Samberg.

The Desert Years of Noah Purifoy (1998)

by Abby Wasserman

The first two things Noah Purifoy did after moving to the desert 10 years ago were to plant a cactus garden near his front stoop and build an adobe wall for a workshop. Then the long-time Los Angeleno cast around the surroundings for his art material of choice--junk.

But the town of Joshua Tree, Purifoy found, is a serious recycling community. No plastic, aluminum or glass clutters streets or backyards, and the local dump is slim pickings. The paucity of materials was an unpleasant reality. He had to buy all new materials, which meant living from paycheck to paycheck. The monotonous brown stretching for miles oppressed him; the silence was unfamiliar; the ceaseless wind knocked down sculptures he erected; and, although he's not a colorist, he yearned for green. He had visited Joshua Tree many times, but moving there caused a kind of root-shock.

During the next months the quiet settled slowly into him, and he adapted to the wind and the long, low profile of the land. The desert became home and studio, and his work blossomed forth. He now sees in his brown surroundings "just brown," and there are art materials to spare since a reporter wrote a feature about him for the local paper. "People started to bring stuff faster than I could catalog it," he says. He buys a few things he can't get any other way--paint, cement, staples, brushes, and the occasional treated post.

The retrospective exhibition Noah Purifoy: Outside and in the Open, organized by the California African-American Museum in Los Angeles, has been on the road since January 25, 1997, and the Oakland Museum of California is its final stop. Curator Lizzetta LeFalle-Collins writes that the title was inspired by Purifoy's statement about his creative process: "Whatever comes up, comes out."

"Inside out," she writes, "also refers to the sense you get . . . that the artist has peeled back the skin of a piece to reveal its interior life. In the more open works, through which you can see the landscape, you feel as though he has broken down the artificial barriers that in cities literally separate the indoors from what is outside. Instead he creates structures that seem to breathe the pure high desert air."

In the 1960s, Noah Purifoy made a conscious choice not to draw, and not to buy new materials for his art. Used and discarded objects with histories, their surfaces worked on by time and circumstance, appealed to him. Junk is plentiful, cheap and evocative, and the used object gathers resonance as it passes from owner to owner. It was a political statement, of course. He is also aware of the irony of having the luxury to choose to work with salvaged materials, while those who are poor have no choice but to scavenge.

Noah Purifoy's home is five minutes from town. Each paved road on the way lasts a certain distance, then turns into dirt and trails off, disappearing into the desert. His place is marked by the sculpture that rises from the desert. Long brown hills bump along the horizon. The weird forms of Joshua trees, resembling T'ai Chi practitioners (the Mormons, passing through, claimed they looked like Joshua praying), grow no other place on earth. It's early May and they're blooming now, as are yucca and cactus plants. Winter rains have caused a high desert flowering, a patchy carpet of low-lying yellow, red, purple and white.

Noah Purifoy walks down his driveway with a greeting and a strong and calloused handshake. Sizing me up, he says, "Call me Noah." As we sip cold water in his mobile home, he wants to know what I'm interested in, which is to spend a couple of days with him talking and observing. He nods, reflects, and suggests a tour around the sculpture garden and then lunch at the Country Kitchen. He likes to work alone; it's a matter of concentration. So it's unlikely I'll be able to observe him working, but I can ask him "anything." He's self-contained but friendly, with the courtesy and soft accent of a southern gentleman, which he is. He was raised in Alabama.

As we walk purposefully around the garden, Purifoy's creations greet us. There are dozens of sculptures reclining, suspended or free-standing. Many are anchored by guy wires or set in concrete to counter the wind. The array of materials is astounding: glass bricks, Astroturf, cardboard, newspapers, chicken wire, sticks, old windows, burned wood, adobe, aluminum, bowling balls, clothing, foam rubber, iron, shoes, tribute plaques, bicycle parts, tires. Oddments combine with oddments, old with new, and each time we walk in a different direction the kaleidoscope of forms shifts.

Purifoy, 80, is a teacher and philosopher. He has three college degrees--one in social science, another in social work, and the third in art, from Chouinard Art Institute. From the beginning his artwork has connected with community. He believes creativity is everyone's gift. Art is a process of problem-solving, finding new solutions to old problems, and in that sense art is at the heart of education. He also believes the journey to being an artist is won only through hard work, and perhaps one never becomes entirely worthy of the name.

He works on three or four sculptures at a time, small assemblages and large installations, inside and outside. "There's less monotony that way," he explains. He is in good health and strong, doing work that would daunt many a younger man--lifting and pouring buckets of cement, hoisting heavy posts, climbing ladders and digging holes. He works virtually alone.

"Cathedral" by Noah Purifoy.

Purifoy is making up for the 20 years of time lost to his own art when he worked fostering creativity in others as a teacher and a founding member of the California Arts Council. The word "lost" isn't quite right. It's true he wasn't doing his own art during those years, and it's true that he would be better-known now if he hadn't put his creative energies into public work. At the same time, those years were a time to fill up with ideas and find new ways to give them form. Perhaps the artist and the community activist in him always had collided. He was disenchanted with the commercialism of the art world, so he decided to step off the fast track. Appointed to the California Arts Council by Governor Brown in 1976, he spent the next 11 years helping develop and fund CAC programs to benefit artists and promote art education. Three of these--Artists in the Schools, Artists in Communities and Artists in Social Institutions--continue to be funded.

The wind is light but we're immersed in sound, a persistent flapping like clothes on a line, high and low-frequency clinks and thuds, like wind chimes of glass, tin, wood and rubber, that issue from moving parts around the garden. Some sculptures lay parched on the desert floor, so sun-bleached that one wants to offer them shade and a lemonade. Others are right at home, such as "Two Similar Belief Systems Face To Face," three tall crosses facing off three spindly voodoo fetishes; "Igloo," a shelter of twigs and sections of white siding; "Indian Burial Ground," which shows, in dissimilar mirror images, burial above and below the earth.

The sculptures are their own community. Birds and jack rabbits have adopted them. Erected in open space, exposed to the elements, they are wide-open to interpretation. They are launched from the deep inner space of Purifoy's intellect, which is itself a structure of broad revelation and delicate concealment.

"Cathedral," a beautiful small building of weathered wood with a creased roof, seems to personify this contradiction, as it has no door or window. "The White House," on the other hand, is open to the sky--but all but one of the windows in its single outer wall are sealed off with clothes or boards.

"Mondrian," of aluminum door-frame parts, is all openness, like a line drawing in space. The joke is that many of the lines are crooked. "I wanted to kick the Mondrian habit," Purifoy comments. The wind has brought down "Mondrian" five times, and each time he reconstructs it differently. Other sculptures fall and he leaves them be. "I do my best to make it stable, but if it falls apart"--he shrugs--"I'm sorry."

Because he has so much space in which to work, many of the newest pieces are environmental in scale. "Collage," a 30 x 60-ft. prone frame filled with clothes bleaching in the sun, can only be appreciated fully from the air, and indeed, helicopters of tourists sometimes circle Purifoy's sculpture garden. Clothes provide the only color in many of the sculptures: following Duchamp's principle of "ready-mades," Purifoy doesn't attempt to manipulate color. Back in Los Angeles in the '60s and early '70s, he painted mostly in black.

"I'm interested in observing how nature participates in the creative process. I observe the changes as the year goes by," he says. "Changes are an integral part of life itself. You have some rather unexpected events and have to make adjustments to them." "Shelter," built into the ground, looks like a crash pad for the homeless, I tell my host. Inside, I step along gingerly, past old cots and hanging remnants. "It's more like a 'blind pig'," Purifoy says, explaining that a "blind pig" is an illegal basement casino. He comments as we emerge into the sun, "It's a common experience for black people to be homeless. My family lived in two rooms and moved many times. So this is a replica of what I've seen and lived with."

There were 13 in his original family, but he can remember only 11, so two must have died young. He's close to his living sisters, who "love me to death." He never married, he says, because "I made the mistake of bringing home every girl to my sisters and they killed her with kindness. I knew what that meant." He chuckles.

We come across "Carousel," round like its namesake and painted in bright hues. "Why the color here?" I ask. "I made this for a seven-year-old who is one of my favorite artists in the community," Purifoy replies. The child is Fawn, the granddaughter of his good friend, artist Deborah Brewer, who owns the land and lives next door.

Brewer was involved in "66 Signs of Neon," a collaborative project Purifoy and Judson Powell organized after the 1965 Watts riots. During the violence and destruction of the riots the men were at the Watts Tower Art Center, which Purifoy founded and where they taught. Afterwards, driven by an impulse they didn't fully understand, they went out into the streets and picked up pieces of still-smoldering rubble and shards of melted neon. Then they invited a small group of artists, consciously including whites, to create art. Finished in just a month, "66 Signs of Neon" was an ode, a dirge, and a rising phoenix. In fact, one piece was called "Phoenix."

"We wanted to tell people that if something goes up in flames it doesn't mean its life is over," Purifoy says. "I've had two good ideas in my life and one was 'Neon.' The other was making environmental sculpture in the desert."

"66 Signs of Neon" traveled to nine California universities from 1966 to 1968, and Purifoy and Powell went along. It was accepted for display in student unions, not art galleries. "It was before its time," he says philosophically, but there's a trace of bitterness in his voice. In those days and for a long time afterward, assemblage and black political art were not regarded as "true" art and were marginalized. The atmosphere in the student union, however, as opposed to the rarefied ambience of the art gallery, may have encouraged people to respond freely, as they did both in person and in comment books.

"You people, citizens of Watts, Los Angeles, USA did it--saw art in a calamity or made it so. You found good where only destruction and oppression prevailed and prevails still. The highest form of the artistic spirit is here in abundance."

"Sure they may be interesting to look at but who the hell can honestly say it took talent or a unique insight into life to pick up something of [sic] the ground paste onto something else and tell you you don't understand art & its deepest meaning if you don't like it ......"

"Mr. Purifoy's #30 is for me the most expressive item here; birth, life, and death people treated as no more valuable than empty bottles, kicked out of the way, smashed for the fun of it, utterly ignored with no feelings of remorse--as long as they are out of sight..."

Windows from The White House by Noah Purifoy.

When the tour ended, Purifoy tried to find a permanent home for "66 Signs of Neon" without success. Finally, he consigned it to the trash man, and so it returned to its origins as junk. It lives in after-images, imagination, photographs, reviews and comments; and in one recreated piece that is traveling with the current Purifoy exhibition: "Sir Watts II." This faceless and armless bust, crowned with a German helmet, originally boasted a chestful of safety pins. Now its chest contents are computer chips. "You can't duplicate with found objects," Purifoy points out; but he could have used safety pins and decided not to. The materials surely expressed changes that had occurred in him. For one, following the tour he was invited to be artist-in-residence at University of California, Santa Cruz. He spent three years teaching, advising, and, he says, finding himself. He was 40 years old. "This was the time to do it. You weren't alone. A lot of people were struggling to do the same thing." With the unwavering friendship of U.C. Santa Cruz Provost Page Smith and his wife, Eloise, who had invited him to the university, he set about with determination. "When I revised my life story, I turned over every goddamned stone that I could find," he laughs. "Every experience was valuable." Much of it had to do with getting out from under the overlay of religion to find his own belief system.

"Martin Luther King was programmed to be who he was," Purifoy reflects. "Someone had ideas for him. I grew up the same. Someone wanted something for me before I was born. I wanted to be good on my own. My mother was a religious person and a good person. She didn't particularly impose her belief system on us except she went along praying silently and sometimes out loud every day that I can remember. So it rubbed off. I was good without knowing why. It disturbed me, so I set out to reverse it. I participated in activities considered bad. I was trying to test myself and the people around me. I chose an elite place to do it in. I tore my ass going and coming to see what the results would be. But it was the '60s." He pauses and nods. "The expression 'you got over' meant that whatever you were looking for you found. And you attribute the discovery to the people who allowed you to do it. It was a glorious experience. One does what one must do to become oneself, even knowing the consequences. You're making the supreme sacrifice so you never have to sacrifice again."

The Country Kitchen on 29 Palms Highway is shabby but homey, with found-object decor, a handful of tables and a tiny counter where they serve breakfast all day. Purifoy is a regular. We tuck away quantities of pancakes, sausage, eggs and coffee as the sun streams in. He reflects on the application of the creative process to general education. "On television we see a problem solved in an hour and a half in front of our face," he says. "Writers reach into their bag of tricks to find a new way to solve some problem we're all familiar with, and each time we see it solved we get a charge out of it. Purists say it contaminates art to say it's something anyone can do, but to us, art is a problem-solving device. We do it without even thinking about it. We use it every day."

I suppose that one of the beauties of assemblage--the putting together of found objects--is that anyone can do it. We use this medium often at the museum with children in our educational activities. Because art is a process of problem-solving, material is almost incidental. Why gnash one's teeth over materials when, as an art critic once told me, the irreducible minimum is the idea?

That night I bring a little book of Purifoy's poems to read in my motel room in 29 Palms. He doesn't write poetry anymore but there was a time it was very important to him. It was "pouring out your insides," working through something important, like art. "Seeing" (1967) could be a credo for the socially conscious artist Purifoy is, as well as being a rationale for assemblage:

As always a new way of seeing things

But what and how?

There were no lakes or ponds

No oceans or streams with seagulls soaring.

No beach sand or sailboats

Or bright buildings or broad streets.

But there was junk---piles of junk

All bundled up and neatly packaged;

Scattered out down the railroad track

Glowing brightly in the absence of sunlight

And thus not glowing brightly.

Neat bright bundles pressed hard,

piled high;

Beer can, shattered glass, bottle tops

flat-out,

Foreign object lying there without relationship

To self or any other, aged forms,

Banked up inactivity. Meaningless existence?

If I could see it differently

For what it is or is not

Still flat out and piled up

In another way yet the same way

I'd offer it up.

Then Free I'd be from guilt for letting it

pile up

And scatter out, and separate itself

....... from itself.

In the morning, I drive through Joshua Tree National Park photographing wildflowers on the way to Noah Purifoy's. There are soft halos around the cacti, and the huge, rounded boulders characteristic of the region seem like burial cairns for ancient giants. I'm surprised and pleased when Purifoy allows me to assist him in the workshop, prying out staples from an assemblage (featuring, humorously, a corset and a truss), and outside, holding posts steady as he pours cement. He adds soil and pats around the posts with the back of a hoe, making the cement ooze like hot lava.

"I've come a long way because I believed in my own ideas," Purifoy says to me after we eat lunch in his kitchen. "Now I am a person I like. I don't make an effort to have others like me. If they don't like me, I'm sorry." He stops, backtracks: "I am sorry." We smile at each other. "I never expected to become the person I'd like to be, but I'm close as I can be. The next stop is non-being--and I'm not ready to face that."

He did make a little graveyard in the sculpture garden to try out the idea, he adds, "but I couldn't stay serious. I filled it with little jokes."

Just before it's time to leave I walk through the "graveyard" alone. On a derelict platform, folding chairs have been set up in readiness. An expectant grave, lined with plastic carpet, awaits a coffin. Dusty mounds sport wooden crosses saying "Help Wanted" and "Colored Need Not Apply." We'll all be dust soon enough, including our attitudes and prejudices, it seems to say, but our spirits, soaring in creative work, will remain. The desert knows this every time it throws out, for our brief delight, the evanescent blooms of spring.

Images from top:

1. Cover of The Museum of California magazine, Summer 1998. Noah Purifoy photographed by Joe Samberg.

2. "Cathedral" by Noah Purifoy. Photographed by Abby Wasserman.

3. Windows from The White House by Noah Purifoy. Photographed by Abby Wasserman.

Originally published in The Museum of California magazine.

No reproduction without express written permission of the Oakland Museum of California.