Reunion in Colombia

Return to Dibulla

Published in the Friends of Colombia Newsletter in three parts: December 2008, May 2009 and December 2009.

Part One

My little Ana is a grandmother. There’s white in her wiry black hair and she is missing teeth. It wrings my heart to see her so fragile. Ana was my little companion in Dibulla, La Guajira, Colombia, in 1964 and 1965, during the year and a half I was a Peace Corps Volunteer there.Ana’s younger sister, my goddaughter Clea, is tall and robust. Mentally, she is still a child. She lives under the watchful eye of her mother, Ida. The last time I saw Clea she was a plump baby, light-skinned and blue-eyed. Her mother and I joked that she was my child. Now, one blue eye has migrated to the right and there’s a cavity in a front tooth. Upon seeing me, she cries, “Aquí está mi madrina! Te quiero, Madrina!” (“Here is my godmother. I love you Godmother!”) My comadre states that Clea has been talking about me for the last three days. Since I haven’t been in touch since 1966, I figure she found out about my return to Dibulla about the time I did, a few days earlier on February 5 in Cartagena, when Haroldo and Pat Suárez told me I could visit my site. I’d been advised it was too dangerous to travel to Dibulla and had swallowed my disappointment and attended the PC-Colombia reunion anyway. So when Haroldo said, “You are going,” I burst into tears. For more than a minute I couldn’t speak. My depth of feeling surprised me.

Alba Lucía Varela of Fundehumac and Haroldo, President of The Magdalena Foundation, had arranged my visit—one day's ida y regreso in the company of a TV journalist and native Dibullera named Lilibet Roca Redondo; her brother Carlos, her cameraman; the driver, Armando; and María Choles Toro, a native of La Guajira who lives in Santa Marta. A victim of violence during the recent tragic decades in Colombia, María has suffered during the last decade. Through Fundehumac, she and her family are going forward with their lives and helping others.

Ida is in her 80s but I recognize her at once: the humor in her eyes, challenge in her shoulders, determination in the set of her mouth. She utters glad cries as we embrace, and then pronounces, "Si me muero, Comadre, tú eres la madre de Clea!" (“When I die, you are Clea’s mother”). Whoa, I think. Aren’t godmother duties over when the godchild reaches 21? Clea’s twice that age. But if the child never grows up mentally? In the midst of my joy at being in Dibulla again, I’m sobered by Ida’s statement. It doesn’t help that Maria immediately challenges me within everyone’s hearing, “Qué vas a hacer para Clea?” I keep quiet. I’ve just returned, after all. I need time to digest what’s happening before making new commitments!

In my PCV days I was wary of requests for personal help. I knew that if I was generous to one family, others would hear of it, and I didn’t want to play favorites or be known as la gringa rica, either. Dibulleros were resistant to change and there were many feuds in town. I could call a meeting of mothers and girls to talk about forming a girls’ club, only to find that few attended. Some had been enthusiastic in conversation, but they wouldn’t attend a meeting if their enemy, Fulana de Tal, was going. The people were extremely resistant to working together in those days.

When I lived in La Guajira, July 1964 to November 1965, the only way to get from Dibulla to Santa Marta was by sea. From the Guajira side, a dirt road petered out at Palomino to the west. I once made the trip to Santa Marta by cayuco (motorized canoe), 10 hours, as I recall, during which a crew member bailed constantly with a coconut shell. Now, In our snug taxi, the five of us breeze along the highway that links the state of Magdalena to La Guajira. It’s a proud and beautiful road. Carlos, Lilibet and Armando assert that it’s the best in all Colombia. I wonder why a first-class highway has been built to one of the country’s most remote regions. Since I was here, coal has become a big industry, and daily loads of it are transported by road and rail. What else? Contraband from Venezuela? There was plenty of that when I was in residence. How about cocaine processed in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta? Is this the road that drugs built?

During one of our stops en route, near the entrance to Parque Tairona, Lilibet prepares a batch of questions and Carlos tests the light. I notice my hands clutching each other. I breathe deeply, trying not to let nerves paralyze my Spanish, which has lain largely dormant for decades. The fact that the words flow more or less correctly is a tribute to the classes I received during PC training at the University of New Mexico.

I was the first female PCV in La Guajira, joining Howard Converse and David Fletcher of Colombia XV who had gone a few months earlier to identify possible sites for acción comunal. We had trained together in Albuquerque, and after talking with them about opportunities in La Guajira, I requested a transfer to RCD from ETV. My six months in Bogotá working in elementary schools to help teachers utilize the new ETV programs had been productive, but I didn’t like city life and longed for a “classic” Peace Corps experience—a rural one. In those days, CARE was administering the urban and rural community development programs for Peace Corps. The new CARE-PC director, William Rayman, after getting country director Chris Sheldon’s approval, okayed my reassignment. I was sent to train with Faye Hooker and Joan Mansfield in Usiacurí for some weeks before embarking for Riohacha, a hot, dry outpost with a newspaper, a gorgeous beach, a working pier, and an uneasy and unequal relationship between the costeños and the native Guajiran (Wayúu) Indians.

Howard decided a male-female team would be effective in Dibulla, while Dave moved to Barrancas in the interior of La Guajira. I made contact with the teachers and started forming relationships with women and girls, and we both consulted with town leaders. The beginning was promising and I relied on Howard’s experience to guide me—but soon he was made a Volunteer Leader and left the Guajira, and I was alone in Dibulla for six months before another PCV, Willie Dow, was assigned to the site.

Our taxi crosses from Magdalena into La Guajira. The day is warm and fragrant through our open windows, the foliage on either side is lushly green. We get our first glimpse of polychrome sea—greens, blues, a touch of turquoise. I feel so happy, like I’m coming home. Along the road there are hectares of banana trees, clusters of fruit covered with blue or white plastic, like bagged, hanged men; and many cattle, thin and hardy, with a Brahma-like hump behind the head. We pull into Rio Ancho, where I used to go nearly every week to work with the community. The bucolic village I knew is gone. In its place, sprawled on both sides of the highway and along the river that gave it its name, there’s a chaos of lean-tos and dilapidated stucco buildings, the paint worn or pocked with bullet holes. We turn to the right onto a road of deep ruts but don’t drive more than 20 or 30 yards before it peters out. Rio Ancho in 1965 was a settlement of a dozen or so new wood and palm huts, rudimentary but practical, sides open to catch the breezes. The site suffered from biting sancudos (biting flies), and all the girls and women wore trousers underneath their dresses. There were no latrines, no infrastructure, but there were a general store, a small junta, and a nascent sense of community. Unlike Dibulla, a stable town built on a grid with its own church and police station, where people were born, grew up, and stayed to raise families, Rio Ancho was a new place mixing refugees and fugitives from La Violencia.

The best house in the village belonged to Manuel Martín, nicknamed El Martillo, The Hammer. A formidable, silent man who never smiled, he was from Antioquia, where he had been (people said) a bandit. This did not frighten me away, but I treated him with respect. I came by bus to Rio Ancho once every week or two, and though I hung my hammock in the home of Clara and Berto, a kind and generous couple, I usually ate breakfast at El Martillo’s house. His wife made oatmeal with milk, lemon peel and a cinnamon stick, and she and her daughters generally sat around watching me as I ate, talking companionably. Clara and Berto once took me on a horseback trip through the jungle to the sea, past fields planted with pineapples. Riding through the jungle, we had a quick, magical glimpse of a jaguar.

In the old Rio Ancho you could sit outside with other women making blood sausage—packing rice and blood into cleaned intestine—and watch the world go by. Aside from swarms of the tiny, vicious sancudos, Rio Ancho was a kind of Eden. Some of the people were even willing to work for the good of the community, having come from cooperative communities in the interior. José de la Paz García, for example, took a leadership role, helping me and a few others organize a school.

As Armando turns the taxi around to leave, Lilibet and Carlos tell me that the people of Rio Ancho were vulnerable when the violence began in La Guajira because their village lay right on the path from the Sierra Nevada. Their relationships were loosely woven, so paramilitaries and drug lords could divide and conquer. There were killings and kidnappings and stolen land. I would like to ask someone if José, Clara and Berto survived, and what happened to El Martillo and his family. But the ghost of recent violence, and the knowledge that we will have only a few hours in Dibulla, hasten us along. We have been told to return to Santa Marta by nightfall. So we bump back on to the highway. There’s a sense of unease in Rio Ancho, as though violent men have only moments before passed through and will soon return.

Part Two

As we approach the Dibulla turnoff, Lilibet tells me that when paramilitaries tried to establish a base in town, they were rebuffed. "We don’t want you here" apparently is all it took to bar their entry. It seems fantastic. If Dibulla could bar paramilitaries, avoid the kidnappings and murders that have plagued La Guajira, why couldn’t other communities do the same? It’s a vexing question and there’s no way I’ll find the answer in a three-hour visit.Nine years ago when my site partner Howard returned to La Guajira, his driver refused to turn into Dibulla, saying it wasn't safe. Now we rapidly cover the six kilometers on a paved road. The landscape is altered: hectares of plantain trees have been cut down and burned. Carlos says the landowner will cultivate rice, diverting water from the Dibulla River to flood his fields. Water levels in Sierran rivers, including the Dibulla, are low due to siphoning off by cocaine producers in the mountains. The rivers are weakened by the time they empty into the ocean, so the strong saline tides push their way further inland.

As though in a dream the new Dibulla comes into view, and as if summoned by magic, Rubiela Raggonessi appears on a tiled porch. At Lili’s command Armando stops the car and we get out. Rubiela, born long after I left Dibulla, is a surprise. Her father, Camilo, was my closest associate. Half-Italian, a Dibulla native, he was a quiet, transformative force and universally respected. He knew everyone’s story. An optimistic realist, he chaired a shifting, loose-limbed junta, working for change without expecting it. It meant everything to have such an ally. Camilo’s wife at that time, Gertrudes, was an Italian who never embraced her life in Colombia. I spent hours in their enclosed garden talking with them and Father Bernardino de l’Aguila, the young Italian priest. Though we sparred constantly, the Padre and I liked each other. He was skeptical about community development and asserted that the people of Dibulla would never change. He didn’t actively oppose my work and sometimes helped, but kept a light and mocking distance.

Rubiela, the child of a second wife, is a proud, handsome, reserved woman with cat eyes. She has a leadership role in the community and is waiting for the midday bus; she has an official meeting in Riohacha. Dibulleros were resistant to working together—there were too many ancient grievances among the families—and cynical about regional government and politicians. They’d suffered more than their share of broken promises and half-finished official projects. Their lethargy was born of disappointment and the easy existence on the coast. The river provided water, the climate was hot and humid, with ample seasonal rainfall; a simple adobe house with a dirt floor and hammocks provided comfort; and fish, fruit, and root vegetables were abundant. The elementary school was run by a kind and generous teacher whom everyone loved. A small police force resided in a building of its own, and the electric plant’s generator once had worked and might again.

On the other hand, sanitation and medical care were abysmal. Everyone had intestinal parasites which sometimes were fatal, and tetanus was a constant danger. The diet was monotonous, mostly fried food. One cow was slaughtered each week, and the meat sold out before noon. Sometimes a pig went under the knife, sometimes a chicken, but they were seldom offered for sale to the public. Many families owned chickens, we’d call them free-range; they fattened on worms and cockroaches and eventually were killed for sancocho, a chicken stew with plantain, yucca and potato—universal celebration fare. There were outhouses but no trash collection; garbage was tossed into empty lots and rotted there, foraged by roaming dogs and pigs. An "auxiliary nurse" took care of minor wounds and maladies, but any serious case was sent to Riohacha, where nuns and a single doctor ran a small hospital. If you needed urgent care in Dibulla after the morning buses left, you were out of luck. The baby next door was born with difficulty breathing (perhaps Hyaline membrane syndrome) and died the same day. There was a lot of drinking and that led to violence. In some circles there, if a member of your family had been killed, you were justified seeking revenge on some member of the killer’s family. In that Hatfield-McCoy code, there were no innocents.

I have brought photos, mostly of children from the ’60s. As people come by—word travels fast that la gringa has returned—they identify them. One is of Juana Bueno, who because of her senility was called Juana la loca. Two grey-haired granddaughters and a great-grandson are pleased to see her photo. Juana used to arrive at my house in the morning, march through to the patio, take out a propane stove, tin can, and oatmeal from her bundle, demand water from my outdoor faucet and hunker down to cook her breakfast. She would eat, wash out the can, pack her belongings and without a word take her leave.

Distinguished, portly Nicolás Redondo turns up to greet me. Only 18 when I arrived in Dibulla in 1964, he is now a prominent citizen, director of the colegio. We are mutually delighted and keep patting each other’s shoulder. He urges me to return to stay again. He says Dibulla still needs me, that yes, there has been progress, but there’s much more to be done.

We drive a few blocks to my old house. Only the color is different. The owners aren’t home and I’m just as glad not to have my memories of its interior jolted. It was one of the best houses in town; now most of the others are upgraded, also made of stucco and tile. The streets are paved for the most part and there are running water and electricity. Across the street at a particularly handsome blue and yellow house we encounter a young woman with a baby. She identifies her family in my photo book; her house is built where their adobe and palm house stood. I almost blurt, "And that one, that tall, unsmiling young man standing next to your mother, shot my friend Cárdenas." Midway through my time in Dibulla Cárdenas came from the interior to take the post of corregidor (sheriff or peace-keeper). Young, handsome, educated, he fell in love with a Dibulla girl whom he planned to marry. One night he encountered my neighbor, drunk and brandishing a gun. He confiscated the weapon but returned it a few days later, and within 24 hours the young man, his macho insulted, ambushed Cárdenas and fled into the Sierra. I want to say that Cárdenas was a good man who cared about Dibulla and that his death was a tragedy, that her uncle was a sinverguenza (without shame), that my friend Chave’s heart was broken, that I sat with her beside the body part of one night in a house cleared of furniture. I say none of this. Why burden her with old griefs?

We visit Olimpia Coronado de Moreu, who with her husband Wilson owned a bus, general store, and the movie theater (now boarded up) where I used to watch U.S. westerns. They were first citizens of Dibulla but kept aloof from community development efforts. She’s in her eighties now, her face softer and more friendly than I remember. Wilson has died. Her daughter invites us in for coffee, but we decline. A cup of tinto would require slowing down to Dibulla time, a luxury we don’t have. I’m sweating profusely. My Mexican cotton dress sticks to my back; it doesn’t catch the breeze like the long, bat-wing Guajiran manta. In mestizo society the Wayuu Indians were considered inferiors. I had a few mantas made, and when I wore them I stood with the Wayuu in a small way that gave me satisfaction but probably compromised my status in Dibulla.

Now, at last, we walk up the street to Ida Campo’s house. This is the heart of my visit. Ida speaks in the fastest, clipped-consonant Costeñan Spanish of anyone I know and is the hardest to understand. Looking around her neat tiled parlor I remember the mud house she lived in, the dirt floor she swept clean with a broom. I recall her father’s wake, my first wake, the shock of seeing people drinking, eating and dancing around the corpse laid out on a table. Ida keeps repeating, "Comadre, you’ve come." She doesn’t ask how I could stay away for so many years or why I didn’t write. My goddaughter Clea, almost my height, holds onto my arm. My eyes strain to see Ana, and slowly, from the shadows, she comes forward, a plump baby on her hip. We embrace and I begin to cry. I loved Ana the most, yet after a year with me I made her move home after she stole money from my mochila, the woven bag that was my purse. The money was returned and I still saw her, but it was never the same. Ana is thin with finely etched wrinkles. Her voice is low and husky and she’s also missing teeth. Yet she still looks like the little girl Ana. "I cried so when you left," she says. "Why didn’t you take me with you?" This is a surprise; was the subject even broached back then? Would I have taken her if asked? No. I married Bill Rayman, had children, moved around the world. Peace Corps was a two-year detour in the life I was meant to live. Or so I thought. The baby is Ana’s granddaughter, one of two she cares for while her daughter attends school in Santa Marta. The highway has made an enormous difference but not, perhaps, for Ana. I ask, "How has your life been?" Ana lowers her head. "He sufrido,", she says.

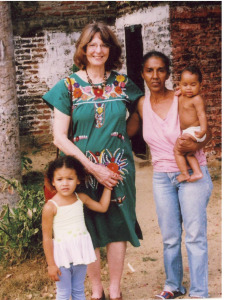

Ana and her grandchildren with the author

Ana and her grandchildren with the authorPart Three

When I first entered Ida Campo’s mud and palm frond hut in 1964, her daughter Ana was 10 years old—dark, thin, and quick to laugh. Now she’s 51 and stands gravely with a grandbaby on her hip. I sense that life has pressed her hard. I would like to be alone with her to talk, to listen, but we’re surrounded by friendly people welcoming me back to Dibulla after 42 years.

Carlos, the cameraman, is taking video footage. Lilibeth interviews me. My goddaughter, Clea, stands close. Ida’s relatives and friends converge. One hour in Dibulla and I’m drowning in sensation and memory. Ana tells me, “Voy a traer fotos de mi familia,” and after I assure her I will wait to see her photographs, she departs. But before she can return, Lilibet says it’s time for lunch, and we leave Ida’s. We walk a few blocks— the street has been opened up for sewer pipe repair—and are welcomed by Rafa and Yuye, Lili and Carlos’s parents, heads of a big and accomplished family.

We’re served cold drinks, and because lunch isn’t quite ready and the cemetery is nearly next door, I excuse myself for a brief visit to what was once my shortcut to the beach. The graves are poorly maintained and crowded with stacked crypts and plastic flowers. I once photographed old Juana Bueno sitting on a crypt, legs crossed, eyes closed, chin resting on one hand. Juana liked the cemetery, too.

Lunch consists of baby shark piccata, sancocho with yucca and tripe, broiled fish, rice, salad, and cold Coca Cola. As their grandchildren arrive home from school, Rafa, Yuye, Carlos and Lili greet them with hugs and kisses. After lunch I visit the family tienda at the front of their house. María asks for dulce de leche, a soft candy made of milk, brown sugar, and coconut, but they haven’t any, so I buy her a hunk of cheese to take home. We walk over to the plaza. Long ago the only gathering place in town was this open field between a row of small houses and the imposing stucco church. PCV’s and people from local government could set up in the field to show films on public health or community development, and folks would bring chairs with them or sit on the ground. Now it’s a real plaza with trees, stucco planters, benches, and a gazebo. A sign on one wall warns against public urination: Tenga cultura no se orine el parque! (Be polite don't urinate in the park!) Padre Bernardino’s church still stands, but a modern new church has been erected next door, with open sides to catch cross-breezes. We do a sit-down interview on the church steps. By this time my Spanish has gained fluency and I’m more comfortable answering questions. Children sidle up to watch; otherwise the plaza is empty during the heat of the day. We proceed to the old abattoir, now an education office, and the police building, which stands behind a high cement wall. There’s a badly neglected basketball court and beyond that the Dibulla River, in which a woman stands thigh-deep washing clothes and a man on shore slices a bicycle tube with a very sharp knife.

Howard Converse, my first Dibulla partner, thought the town had great potential as a resort, and there does appear to be some progress—a couple of beachside cafés and shady cabañas. The cafés are closed but I can imagine lingering in them over cold beer and fried fish. I wade into the river, dipping water onto my wrists and neck. The Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta is hidden by clouds. A bicyclist with a small boy on his crossbar rides slowly through the river shallows.

Dibulla Cemetery

But I’m worrying about Ana. We’ve been gone for an hour and a half and perhaps she will think I’ve left without saying goodbye. So we return to my comadre’s house, where María again asks what I am going to do for my goddaughter. Ida chimes in gaily that I must take Clea to the U.S. I don’t tell her that this is impossible. It’s obvious that someone with reduced mental capacity like Clea is best off in her home town, surrounded by relatives and friends who love her and will protect her.

I will learn later from Alba Lucía Varela how Fundehumac in Santa Marta works with families to set goals and ways to achieve them, and how interested parties like myself can provide money through Fundehumac to support the effort. The key is a personal commitment—theirs. When I hear this I am filled with joy. To work with a family as a whole, taking everyone’s needs and goals into account—this is something I can embrace. I always thought that I was a poor Peace Corps Volunteer. I built no roads or schools or latrines, formed no lasting organizations, bettered no one’s life. I spent a lot of time listening and learning, not much doing. For many of us, our best intentions ended in failure or disappointment. We didn’t understand in those early Peace Corps years how difficult, even impossible, our ambitions were. Now, through the warm reception I’ve received in Dibulla, I realize that just being here and being myself may have been enough. Success has many faces and many hearts. We stop at the Electric Plant across from Ida’s, a sturdy stucco building that also houses the town library. As I admire its neat interior and reconnect with the old A.I.D. generator in the back, a blond middle-aged woman with merry green eyes approaches, saying, “Me acuerdas?” And instantly I do —not her name but her face. I whip out a photo of a little blond girl with green eyes hunkering down in front of my house. “Soy Olga!” she cries, clutching the picture and hugging me. Olga remembers me! What better proof of time well spent?

Armando, the driver, says it’s almost time to leave; we must arrive in Santa Marta by dark. As I’m saying goodbye to Ida and Clea, a man comes up smiling in a challenging way. “Quien soy yo?!” he says, waiting for acknowledgment. But I have no idea who he is. “I don’t remember you,” I finally stammer in Spanish, and his face shuts down; he is hurt. “Enrique Deluque,” Ida cries, “el padrino de Clea!” Enrique! We stood together at Clea’s christening, yet there is nothing familiar about him. Perhaps my mind is on overload. Hours later I will remember him, but by then we’re in Santa Marta. I vow to write an apology. I think, I should have pretended, and then, defensively, It’s 42 years ago, for God’s sake! Nevertheless, this inadvertent insult to an old friend disturbs me.

I understand now the story of Rip Van Winkle. I’ve awakened in a transformed Dibulla stark in its contrast with the past. I’ve had no part of its daily shifts, its gradual changes. I never saw Ana when she married in a long white dress, or Ida when two of her grown sons died, shooting each other during the marijuana wars years, or Camilo Ragonessi when he first held his baby girl, Rubiela, or Padre Bernardino on the eve of his return to Italy, if he ever did return. Our paths were the same for a brief time in the 1960’s, and then parted, to converge on this day in February 2008.

We drive to Ana’s house a few blocks away. Hearing the car doors close, she comes outside to greet us. She asks me inside and I follow. The floor is packed dirt and there’s no glass in the windows. Beckoning me close, she lowers her voice, and I know what she is going to say before she begins. “I have always felt so bad that I took that money,” she whispers. When Ana took 40 pesos from my mochila after we’d lived together for a year, I went to her mother at once, but before I said a word, Ida handed me the money. Ana returned to her mother’s to live, and although we remained friends, I felt my trust had been betrayed while also regretting the severity of her punishment, for I suspected soon enough that my careless habits with money were as much if not more to blame. I place my hands gently on her thin shoulders and talk softly. I tell her it wasn’t her fault, that she was a little girl, that I was just as responsible, that I forgave her long ago. She brightens. How grateful I am to wipe away her guilt, and my own.

“The next time you come, stay with me,” she says. Could I hang my hammock in this dark house at my age? I decide I could. I smile. I promise I will stay with her when I return. Outside she gives me her address and cell phone number. Cell phone! In the old days there was no telephone service in Dibulla. One day all the houses will have proper floors. The sewer system will reach everywhere and everyone will have flush toilets. The roads will be fully paved and there will be a tourism infrastructure. For the Dibulla of today has a sense of itself—it is grounded. It’s the place that didn’t let the paramilitares in. People know what they can accomplish working together. I wave to Ana as we drive away, feeling a surge of love for her and for this place.

As we approach the edge of town María sees two boys carrying a parcel and calls out hopefully, “Tienen dulce de leche?” And like the miracle of the loaves and fishes the boys nod. Armando stops the car and María and Lilibet buy warm bagfuls and hand them around. Like Proust’s petites madeleines, the dulce de leche transports me to Dibulla in the mid-60’s, when I was 23: radio music in the streets, cold beer on hot afternoons, the smell of blood in the abattoir, the black-and-white movies in Wilson’s theater, the bus at dawn to Riohacha, the cool river and warm sea, the sound of thunder at four o’clock in the afternoon, rain pounding the dirt roads, the return of the sun’s warm breath. We speed past the soon-to-be rice fields and onto the highway. As we again approach Rio Ancho, on impulse I ask Armando to turn into town. And there, in the scrawny plaza a chorus of uniformed schoolchildren perform a song for an audience of parents, teachers, and friends. Their sweet voices lift and soar like birds. Like hope.

I will learn later from Alba Lucía Varela how Fundehumac in Santa Marta works with families to set goals and ways to achieve them, and how interested parties like myself can provide money through Fundehumac to support the effort. The key is a personal commitment—theirs. When I hear this I am filled with joy. To work with a family as a whole, taking everyone’s needs and goals into account—this is something I can embrace. I always thought that I was a poor Peace Corps Volunteer. I built no roads or schools or latrines, formed no lasting organizations, bettered no one’s life. I spent a lot of time listening and learning, not much doing. For many of us, our best intentions ended in failure or disappointment. We didn’t understand in those early Peace Corps years how difficult, even impossible, our ambitions were. Now, through the warm reception I’ve received in Dibulla, I realize that just being here and being myself may have been enough. Success has many faces and many hearts. We stop at the Electric Plant across from Ida’s, a sturdy stucco building that also houses the town library. As I admire its neat interior and reconnect with the old A.I.D. generator in the back, a blond middle-aged woman with merry green eyes approaches, saying, “Me acuerdas?” And instantly I do —not her name but her face. I whip out a photo of a little blond girl with green eyes hunkering down in front of my house. “Soy Olga!” she cries, clutching the picture and hugging me. Olga remembers me! What better proof of time well spent?

Armando, the driver, says it’s almost time to leave; we must arrive in Santa Marta by dark. As I’m saying goodbye to Ida and Clea, a man comes up smiling in a challenging way. “Quien soy yo?!” he says, waiting for acknowledgment. But I have no idea who he is. “I don’t remember you,” I finally stammer in Spanish, and his face shuts down; he is hurt. “Enrique Deluque,” Ida cries, “el padrino de Clea!” Enrique! We stood together at Clea’s christening, yet there is nothing familiar about him. Perhaps my mind is on overload. Hours later I will remember him, but by then we’re in Santa Marta. I vow to write an apology. I think, I should have pretended, and then, defensively, It’s 42 years ago, for God’s sake! Nevertheless, this inadvertent insult to an old friend disturbs me.

I understand now the story of Rip Van Winkle. I’ve awakened in a transformed Dibulla stark in its contrast with the past. I’ve had no part of its daily shifts, its gradual changes. I never saw Ana when she married in a long white dress, or Ida when two of her grown sons died, shooting each other during the marijuana wars years, or Camilo Ragonessi when he first held his baby girl, Rubiela, or Padre Bernardino on the eve of his return to Italy, if he ever did return. Our paths were the same for a brief time in the 1960’s, and then parted, to converge on this day in February 2008.

We drive to Ana’s house a few blocks away. Hearing the car doors close, she comes outside to greet us. She asks me inside and I follow. The floor is packed dirt and there’s no glass in the windows. Beckoning me close, she lowers her voice, and I know what she is going to say before she begins. “I have always felt so bad that I took that money,” she whispers. When Ana took 40 pesos from my mochila after we’d lived together for a year, I went to her mother at once, but before I said a word, Ida handed me the money. Ana returned to her mother’s to live, and although we remained friends, I felt my trust had been betrayed while also regretting the severity of her punishment, for I suspected soon enough that my careless habits with money were as much if not more to blame. I place my hands gently on her thin shoulders and talk softly. I tell her it wasn’t her fault, that she was a little girl, that I was just as responsible, that I forgave her long ago. She brightens. How grateful I am to wipe away her guilt, and my own.

“The next time you come, stay with me,” she says. Could I hang my hammock in this dark house at my age? I decide I could. I smile. I promise I will stay with her when I return. Outside she gives me her address and cell phone number. Cell phone! In the old days there was no telephone service in Dibulla. One day all the houses will have proper floors. The sewer system will reach everywhere and everyone will have flush toilets. The roads will be fully paved and there will be a tourism infrastructure. For the Dibulla of today has a sense of itself—it is grounded. It’s the place that didn’t let the paramilitares in. People know what they can accomplish working together. I wave to Ana as we drive away, feeling a surge of love for her and for this place.

As we approach the edge of town María sees two boys carrying a parcel and calls out hopefully, “Tienen dulce de leche?” And like the miracle of the loaves and fishes the boys nod. Armando stops the car and María and Lilibet buy warm bagfuls and hand them around. Like Proust’s petites madeleines, the dulce de leche transports me to Dibulla in the mid-60’s, when I was 23: radio music in the streets, cold beer on hot afternoons, the smell of blood in the abattoir, the black-and-white movies in Wilson’s theater, the bus at dawn to Riohacha, the cool river and warm sea, the sound of thunder at four o’clock in the afternoon, rain pounding the dirt roads, the return of the sun’s warm breath. We speed past the soon-to-be rice fields and onto the highway. As we again approach Rio Ancho, on impulse I ask Armando to turn into town. And there, in the scrawny plaza a chorus of uniformed schoolchildren perform a song for an audience of parents, teachers, and friends. Their sweet voices lift and soar like birds. Like hope.

©Abby Wasserman 2020