Peter Voulkos: Information, Resistance, Confrontation

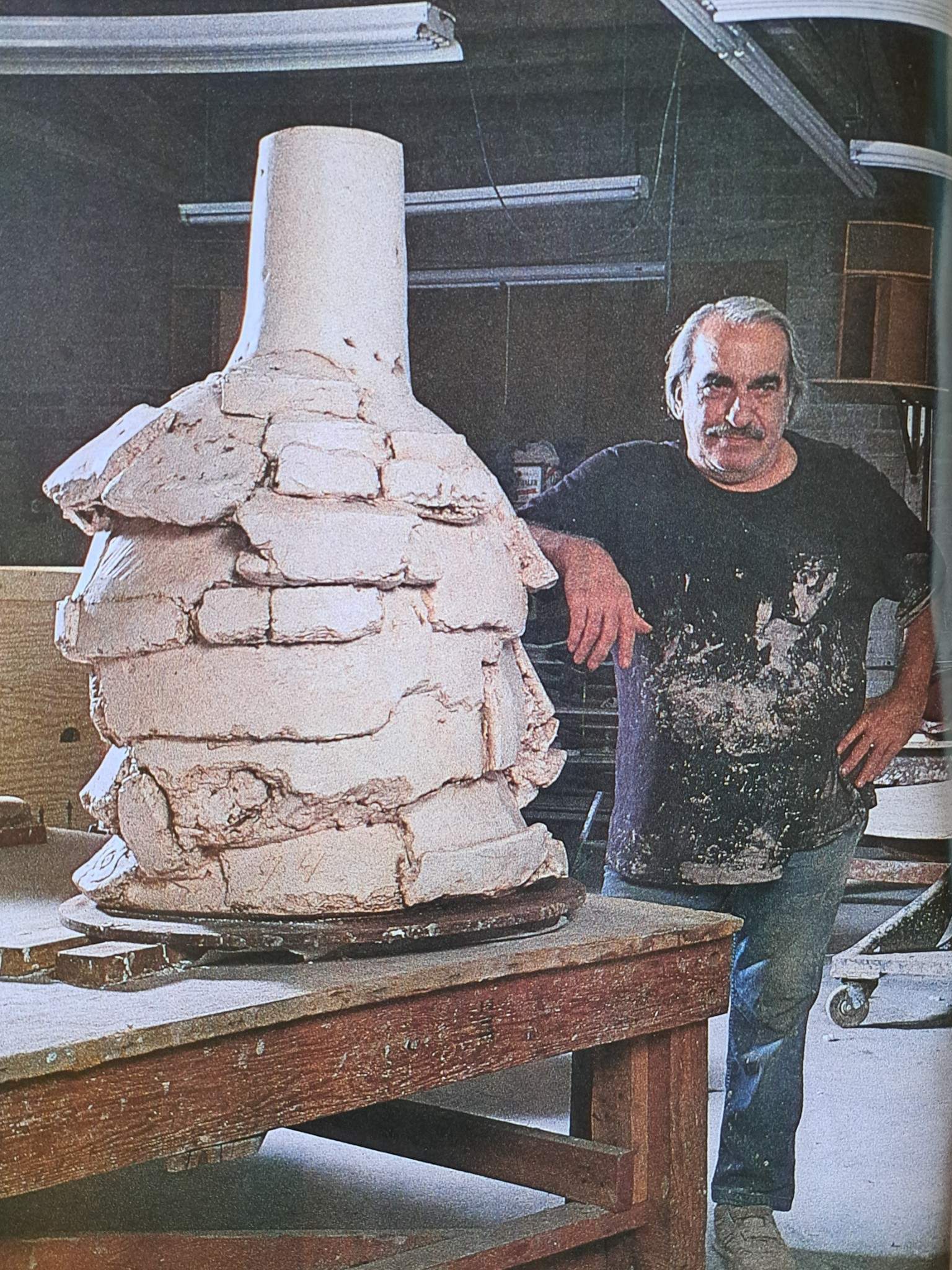

Peter Voulkos in his Oakland Studio, 1995, photographed by Joe Samberg. Click for full photo.

By Abby Wasserman

ARTISTS ARE known by their obsessions—the themes, subjects or materials they employ, consciously and unconsciously, throughout their careers. Style as physiognomy. As a teacher of mine once said, every work of art is a portrait of the artist.

Peter Voulkos and his sculpture resemble each other, at times physically, always intrinsically. His bronze linear work, for example, expresses his musicality (he is a guitarist) and his soaring, questioning spirit. The wood-fired “stacks”—craggy, muscular, earthy—evoke his physical presence. The plate and ice bucket forms, thick and rough, perforated and slashed, recall his ferocious energies.

The work, like Voulkos himself, is multilayered and complex, fierce, subtle and devil-may-care. To know him, study his sculpture. As Oakland Museum curator Karen Tsujimoto writes in her exhibition catalog essay for The Art of Peter Voulkos, “The cues to his personality and style reside less in linear development than in his repetitions and reiterations of critical motifs and key feelings. In this process the artist comes to know himself, and in turn, reveals himself to others.” Voulkos spins ideas like clay on the wheel, confronting them with his eagle’s gaze, wrestling with them until they have given up their information, until they no longer resist. Information, resistance and confrontation are his watchwords.

HE STARTED out as a painter, was converted to clay and became a potter in the classical mode, winning national acclaim. He switched direction, impressed by the energy of attack of abstract expressionist painters in New York, and brought that sensibility to clay in the way the late Alvin Light brought it to wood. Voulkos broke the mold of clay. Still later, he branched out to large-scale bronze casting, though continuing to work in clay. His most recent sustained interest has been wood firing in the anagama, a Japanese kiln that has been used for centuries. He has been exploring three sculptural forms—the plate, the stack, the ice bucket—fired in this way for more than a decade; and has been doing monotypes as well.

“As long as I keep getting information from them I keep doing them,” he says. “The painter has a canvas in front of him, and that’s a particular format. He uses it all the time. It’s the same with this”—indicating a plate—“but you get it in the round here. The stacked forms are a complex shape, a lot of information goes back and forth. It’s got its own ideas. It’s a struggle to get something to come out of it that I can feel is some sort of confrontation. Something floods back into me that makes my life a little bit better than it was when I started. You keep going on until you arrive at some conclusion about it. The problem is to get to the final thing when you can say you don’t know what to put on or take off any more.”

Peter Voulkos is speaking from the curved brown leather sofa in his mammoth Oakland studio early on a Saturday evening, with just an hour to chat before he and his ceramist wife, Ann, have to go out. At 71, Voulkos is all coiled energy. He radiates warmth like a piece of just-fired pottery, and his voice sounds like wet gravel in a wire net. “You sure that things is working?” he snaps, fixing my ancient tape recorder with a glare. He tells me about an interview years ago with Rose Slivka, author of the definitive 1978 monograph on Voulkos (updated for the current exhibition catalog): three hours, a lot of good things said—and it turned out the recorder was on the blink and the whole thing had to be done over again.

He’s alert even when slouching. A friend remembers him once passing non-stop through a room full of colleagues and students, not seeming to notice anyone or anything, but afterwards commenting accurately on everything that was going on. His slender, long-nailed fingers are constantly touching something—a magazine, a coffee cup or a cigarette, which he twirls absently like a tiny baton. The walls, windows, floor and ceiling, sink, tabletops and shelves of his Oakland studio (“The Dome”) are spotted, painted, perforated, gashed and layered. Every inch holds visual interest—information, he would say. He wouldn’t allow a house painter he hired to paint a wall above the studio sink, although it’s a mess of large splotches—the residue of thrown wet balls of clay left over from the wheel—because he likes to look at them; after awhile, figures begin to emerge.

PETER VOULKOS was born Panagiotis Harry Voulkos on January 29, 1924, in Bozeman, Montana, the third of five children of Aristovoulos (Harry) Voulkopoulos and Effrosyni (Efrosine) Peter Voulalas. Harry had arrived in Bozeman three years earlier from the mountains of Thrace, where he fought the Turks in World War I. Efrosine, from the island of Lesbos, arrived a year later for their prearranged marriage. They couldn’t have settled in a more beautiful landlocked place. In the Gallatin Valley, the mountains slip down to cool their heels in some of the best trout-fishing streams in the country. Mere miles away, the buffalo (actually, bison) roam in northern Yellowstone. Voulkos, however, is blasé about the magnificence of his birthplace. “New York skyscrapers are more awesome to me than mountains,” he says. “You take a mountain for granted, but a skyscraper just blows my mind. I came from a beautiful place to start with but I don’t consider it better than going through the worst places in Oakland. Yosemite has beauty, but the strife and crap we go through every day has beauty too. I’d rather be in Oakland than on a mountain.”

Harry Voulkos (in time-honored American fashion, the last name was shaved down) became a celebrated chef in Bozeman and environs, and Efrosine, a sturdy woman with good sense and good taste, managed the home and raised the children. She was happy that Peter became an artist, although at first she didn’t understand how making pottery—“pots and pans”—was being an artist. There are many cultures in the world where art and craft are so inextricably bound with ritual and function that you can’t tell where one begins and another ends. Perhaps her initial response challenged her son to make his 180-degree turn away from classically graceful ceramic forms to experiment aggressively with clay as a sculptural medium. I wonder, too, if he feels a kinship to his father’s ovens and stoves when he fires a kiln.

Voulkos is fascinated by pyramids, burial mounds and volcanoes. He and Ann used to walk in Sibley Park, a part of the East Bay Regional Park system. “It was once an active volcano up there,” he says. “It’s dead, but it was hot at one time. You can see how the lava pushed rocks up.” Transformation by fire. Volcanic shapes appear frequently in his monoprints. You can practically feel the heat pulsing through their bellies and roaring out their chimneys.

AFTER HIGH school graduation in 1942, Voulkos went to work in Portland, Oregon, as a molder’s apprentice, constructing molds for engine castings on American Liberty Ships. A year later, at 19, he was drafted into the Army Air Corps and eventually sent to Saipan as nose gunner on a bombing crew. He talks about air-to-air target practice and how the men would land and examine targets to find out who had scored a hit. Each man’s bullets were marked with a different color of wax. The image remained in his unconscious: he says he’s never made the connection until now, but his riddled plates do look like they’ve been used for target practice.

Voulkos admires birds. He used to dream he was flying. Perhaps, he jokes, he was a bird in an earlier life. He especially likes watching hummingbirds fly straight up or hover. He also admires ants. “I love those National Geographic specials,” he says. “[The camera takes you] down in the hill to watch them. There’s always a scout, and if you watch him, soon they’re all around him. If you don’t touch that guy they’ll be all over the house. I used to spray ’em. Now I leave them alone, let ’em come in. I’ve seen a trail of ’em hundreds of feet long. They’re tireless. Do they ever sleep?”

I see Voulkos out there, the ant scout, finding a new trail that the other, maybe not so imaginative or driven ants he’s surrounded with, are happily following.

BACK FROM the war, Voulkos decided to attend Montana State College (now University) on the GI Bill, majoring in fine art with an emphasis on painting. Awkward at first, he suffered. “I had no confidence in myself,” he says. “I had difficulty drawing. I’d sit there and watch other kids work and turn green with envy. I couldn’t get my hands to go in that way. But I’d study the history of painters and that sort of turned me on. Reading about Van Gogh and others made you want to work.”

He was required—“forced”—to take a ceramics course in his junior year, and it proved a dramatic turning point. “I had a ball of clay in my hand and put it on the wheel and it was like God came down and touched it,” he says. “Something very religious happened. A white light,” he jokes, intrigued but not beguiled by mysticism. “All my energy was sapped into that ball of clay on the wheel. I had no energy for anything else. I had to do this 24 hours a day. That went on for years after that. It’s a difficult thing to explain,” he finishes with a shrug. He used to sneak into the college “mud room” at night after ending his shift at the Burger Inn. He’d slip through a window and work all night as the watchman, whom he had befriended, looked the other way.

Ceramics students at the college were given only 25 pounds of clay per quarter, so they dug their own. Voulkos spent his weekends digging clay and processing it—red-iron earthenware clay from the hills, slip glaze from a canyon outside of town. He was hardworking and inventive from the beginning. As his Montana State ceramics teacher, Frances Senska, told Rose Slivka, “Everything Pete does is based on knowing it from all angles, from there he goes off on his own. A lot of people don’t get anywhere that way, but Pete did because he’d work long and he’d hit something that he didn’t know and, frankly, I didn’t know much more. But he’d come and talk it over; we’d figure out what it was and get suggestions. When he needed something, he went and got it.”

He continued to paint and to explore surface decoration on his pots; he has never stopped. “Painting helps the sculpture, sculpture helps the painting, pottery does both,” he says. “They are all interrelated, although they all demand different disciplines and different kinds of thinking.”

Gesturing again toward a finished plate, he says, “I like to handle materials that I can’t quite control. I could never do this on a flat piece of paper—I need it round and slightly curved. I need the resistance of the clay, and I’m thinking about the possibilities of the fire and everything’s coming into play, it’s very complicated. I’m tactile. I need that kind of resistance. The thing about clay is, it’s an intimate material and fast moving and silent. The quicker I work, the better I work. If I start thinking and planning, I start contriving and designing. I work mostly by gut feeling.”

VOULKOS BELIEVES you can identify a clay person, that there’s a language all clay people understand. The National Council for Education on the Ceramic Arts (NCECA) conference draws three to four thousand people each year, he says. “It doesn’t happen in painting or sculpture or any other art form that I know. We feel a kinship with each other. It just happens that these people like to have their hands in the mud.”

As a young ceramist, Voulkos did beautiful work. In 1950, at only 26, he won one of the most important national competitions at the time, the United States Potters Association Purchase Prize, in the 15th National Ceramic Exhibition at Syracuse Museum of Fine Arts (now the Everson Museum of Art). A few months later he enrolled at the California College of Arts and Crafts (now California College of the Arts) in Oakland for graduate studies in ceramics with a minor in sculpture. He studied with Vernon Coykendall and Henry Lienau, and met fellow students Nathan Oliviera and Manuel Neri.

“At that time he wasn’t doing the type of work we know him for,” Manuel Neri told me during a phone call. “He was influenced by Greek amphoras. His attitude towards the material itself drew me. I saw him give a demonstration in throwing porcelain at Mills. Everyone was doing things that were 10 inches high, and Peter threw something three feet high, something ridiculous like that. Extreme dominance or control of a medium impressed all of us at the time. Remember that in the early days ceramics was very connected to the Orient. Pete came along and brought something way beyond that, but keeping flavor of the hands-on approach of the Japanese. It had to do with bringing out the character of the material with a different kind of attitude. Not brutal. Or if it was, you have to use the word ‘elegance’ with it—an elegant brutality. What first fascinated me was the way he forced himself on the material and made demands. Clay is Mother Earth, and you can get seduced by the goddamn stuff and end up rolling around on it as some of my friends did. He made demands, and that’s why we all respected him.”

On a summer break from CCAC, Voulkos met Archie Bray, Sr., owner of a brick-making firm in Helena, Montana, who was planning to build a pottery art center. Voulkos and two friends from Montana State, Rudy Autio and Kelly Wong, went to work for Bray firing the beehive kilns at the factory, making and salt-glazing bricks in exchange for using the facility for their own work. They also helped build Bray’s new pottery. After completing his MFA degree and marrying first wife Margaret (Peggy) Cone in 1952, Voulkos taught classes and participated in his first commercial gallery show, in San Francisco. Back in Montana he met Japanese ceramist Shoji Hamada, historian Soetsu Yanagi and English potter Bernard Leach, who were on a national tour. Voulkos remembers watching Hamada paint in watercolors outdoors. It was so cold that the water froze on the paper, and Voulkos was impressed with Hamada’s interest and acceptance of the resulting patterns.

PETER VOULKOS’ LIFE is a lot like his own description of the experience of making a collage: “There’s a flexibility to a collage, akin to working with pottery. You cut pieces and tear pieces and put them on top of each other, and it changes with every piece you put on. You tear the stuff off the back and bring it around to the front. You’ve got thousands and thousands of possibilities—it just snowballs.”

In 1953 his life was an expanding galaxy. He was gaining a national reputation as a ceramist, meeting heroes and learning from them. He had put down roots in California, where he would eventually settle, and he and his wife had a baby daughter, Pier. Just when it was hard to figure how it could get any better, he was invited to teach a summer course at Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

To be prominent it’s important, maybe essential, to be in the right place at the right time, but time and place don’t determine the quality of a life. Just as important are aspects of personality—talent, determination and an attitude towards safety and risk. Voulkos trusted his instincts, but he also prepared for eventualities before forging ahead unafraid. He had become a master at his craft, Slivka writes. “His influences were far-ranging, coming both from traditional and contemporary pottery, from ancient Sung, Korean, Native American and Greek to contemporary Swedish, Italian and Japanese ceramics. No era passed without value in it for his work, and no art or craft, whether carpentry, weaving, plumbing, painting or sculpture, was ignored. Voulkos learned and still learns from everything.”

When technique is mastered, the artist is ready to find his or her own path, like the ant scout. At Black Mountain College, the interdisciplinary, experimental school founded in 1933 by John Andrew Rice, Theodore Dreier and others, Voulkos met avant-garde composer John Cage, dancer/choreographer Merce Cunningham, poet Charles Olson, poet/potter M.C. Richards and others who would have a profound effect on him. In that richly liberal atmosphere Voulkos, Slivka writes, “acquired a fresh outlook on art and attitude toward experimentation that were to release his own adventurous spirit and fierce energies.”

After the summer session, M.C. Richards invited Voulkos to visit New York. He saw Cage again and met painters Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Robert Rauschenberg, Phillip Pavia and Jack Tworkov, and frequented the Cedar Street Tavern, 5-Spot, Dillon’s Bar and other watering holes of abstract expressionist painters and jazz musicians.

That fall he walked away with the top prize in ceramics in a Brooklyn Museum show called Designer Craftsmen U.S.A. 1953. Yet even as his ceramics were winning prizes, he was moving towards the avant-garde. “I was young then, and susceptible,” Voulkos told Slivka. “I had everything to learn. I was dumbfounded by the energy coming out of New York painting in the fifties. After seeing that, I really got excited about some new possibilities for clay. You didn’t have to make soup bowls. Or, if you did, they could be exciting things.”

Karen Tsujimoto believes that among the lessons Voulkos absorbed from his exposure to the New York School was the fundamental belief that art, once one has mastered the moves, is the result of unpremeditated actions. “For Voulkos the act of creation itself—that transitory moment when paint is flung onto a canvas or clay is attacked and formed—is most crucial,” she writes. “While the resultant art object is important, the energy of the experience is of paramount value to him.”

IN AUGUST of 1954 painter Millard Sheets, director of the Los Angeles County Art Institute (now Otis College of Art and Design) invited Voulkos to head a new ceramics department and graduate program. Paul Soldner, his only student for the first month, worked with Voulkos laying out the facilities, building a prototype electric wheel and designing kilns with the help of a ceramics engineer, Mike Kalan. Other students quickly signed up—Malcolm McClain (Mac McCloud), Joel Edwards, Billy Al Bengston, Michael Frimkess, John Mason, Kenneth Price, Janice Roosevelt, Jerry Rothman, Kayla Selzer and Henry Takemoto.

The following spring, Voulkos won a gold medal in L’Exposition International de la Céramique in Cannes, the only American to do so. Again, the accolade was for innovative ceramic, the kind he was about to abandon. He spent the following summer in Montana working at the Bray pottery and experimenting with stacked forms, manipulating and combining thrown and slab elements. In the fall he returned to Los Angeles.

In those days Los Angeles was a sleepy place, lacking a supportive infrastructure for artists. There were almost no galleries, patrons or art schools, which is why the LA County Art Institute was so important. Voulkos, whom Sheets had hired on the strength of his work to date, stirred things up. For the next few years, until he was asked by Sheets to resign his position because of ideological differences, he experimented increasingly with large-scale ceramic sculptures, eschewing small, precious forms. In 1957 he met Rose Slivka, who subsequently became editor-in-chief of Craft Horizons magazine (now American Craft). He also met Fred Marer, a Los Angeles college mathematics professor who began to collect Pete's ceramics as well as work by his students.

Manuel Neri tells me, “When I finally got to Los Angeles to visit him, I was amazed at the people he gathered around him, painters who became representative of Los Angeles at that period—Ed Kienholz was a strong friend, Kenny Price, Billy Al Bengston, John Altoon. It wasn’t just that what he was doing was a strong force for them, but that he was the only force. The influence of the Mexican muralists was dying off, and it was a complete vacuum. People were desperate to look around to see something, talk to somebody, have rapport, and Peter Voulkos at that ceramic shop was the center.”

Then, as before and since, the charismatic Voulkos gave demonstrations and workshops all over the country. He loves to share his process, the moments of creation. In the catalog for The Art of Peter Voulkos, Slivka describes such a session in lively detail, comparing his work in front of an audience to a jazz musician improvising before his listeners, that “precise reflex of knowledge, experience and timing” that can only happen when one has mastered a craft. Voulkos doesn’t explain what he’s doing, just does it, talks if he feels like it, and if a piece collapses, which is rare, he junks it, joking with his delighted audience, “Like my mother used to say, ‘It won’t get well if you pick at it.’”

He doesn’t like to work in isolation. “I like feedback, audience feedback. I feel their energy coming at me,” he says. “Even in the middle of the night I have someone with me, helping me. I rarely work alone, except in the years when I first started in the basement of the school. I was very shy and timid, I couldn’t do anything right. I remember the first time I worked in front of people. I was so nervous! I was shaking so I couldn’t get the clay up over six inches. I said, I’ll never do this again in my life. But when I went into full-time teaching I had to do it. It’s a great teaching tool.” He chuckles, twirls his unlit cigarette. “Why are people watching this old guy with mud all over his clothes? What is it?”

Paul Soldner gave a name to the Voulkos demonstration: osmotic education.

AS A TEENAGER Voulkos played trumpet in the school band, and in Los Angeles he studied classical guitar with Theodore Norman, becoming “somewhat” good—at one point he was practicing five hours a day. His teacher told him he had to choose between clay and music, and he eased off the guitar. In 1982 he resumed, concentrating on flamenco, which he adores. He sometimes talks about his sculpture in the flamenco term of duende, which is that moment when everything—guitarist, singer, dancer, rhythm, beat, melody, grace—works together. “Clay is like music,” he says. “You have to know the structure of music and how to make sound before you can come up with anything.”

The next layer of Voulkos’ life involved bronze casting, interestingly just as he was hired to be a professor of ceramics at the University of California, Berkeley. It’s tempting to relate the bronzes to music, not only because of their timing (once he stopped playing guitar, the music emerged in another form) but because the bronzes are swooping, lyrical and attenuated. Something like Giacometti, whom he admires, or bubble gum when you pull it out of your mouth in a long sticky line and do some fancy twisting.

He had been picked up by U.C. right after leaving his Los Angeles job, joining the renowned faculty of the Decorative Art Department. Continuing to work in clay, he also established a casting foundry, Garbanzo Works, in Berkeley. The names of the bronzes he did in the next decade or so include Honk, Cascade, Mr. Ishi, Solea, Taranta, Osaka, Return to Piraeus, Miss Nitro—a catalog of sound, dance, and travel nostalgia. They do what his clay sculpture never could—invite you, literally, inside. And bronze forms didn’t need a pedestal—they could attach to a wall or any other surface, something very difficult to do with clay. Voulkos finally could work as large as he wanted, and he liked the smoothness, coolness and changing coloration of bronze, and the way it sounds when it’s touched a certain way, the music it makes.

“I feel things,” he tells me. “I have a hand sensibility. I walk into a museum and always have a guard on me because I touch things. Years ago I took people over to the Oakland Museum. I was showing ’em Mr. Ishi. I was pounding on it, and we were all banging it, going yah yah yah yah, and a guard came up and said, ‘You’re going to ruin that sculpture.’ I said, ‘Lady, I made that sculpture. I’m not going to ruin it. You’re supposed to touch it.’ She wouldn’t back off so we left.” He shakes his head. “The kids slide all over it, and it’s in good shape. Sliding on it is good.”

In 1973 Voulkos began work on a series of 200 ceramic plates commissioned by the Louis Honig family in San Francisco, at the same time acquiring a factory building in Oakland, which was developed into artists’ studios and residences. Two years later he acquired a second Oakland building, where he lives with Ann and their son Aris, now 21, their cat (named Dog), and usually one or two of Aris’s friends. Neighborhood kids hang out there, including his son’s music group. They have decorated one huge room with graffiti, and there’s a basketball court. Ann and Pete’s living space is tucked inside the building like pottery in a kiln. The dining room is laid with a brick floor. There are no street-level windows, just skylights they cover with blankets when the sun gets too bright. Their adjacent studios have huge windows, though, and there’s a pretty little garden out back.

IN 1978, THE YEAR Slivka’s monograph was published, Voulkos met Peter Callas, the New York artist who had built a Japanese wood-fired kiln, the kind in which ancient Haniwa terra cotta figures were fired. Intrigued, Voulkos started firing under Callas’ expert guidance. An anagama firing goes on for five days or more, until the wood ash circulating through the chamber melts, coating the pottery with a natural glaze of surprising intensity and unpredictable coloration. In 1984, reviewing Pete's show of anagama pieces, the late San Francisco Chronicle art critic Thomas Albright called them “the most profoundly beautiful and moving things that Voulkos ever has done.” He wrote that they suggest “the actions of an inspired Zen master who has reached an exalted stage where intelligence and intuition, mind and body, design and accident, all come to work miraculously together.”

Karen Tsujimoto observes that wood firing has rejuvenated Voulkos’ love of ceramics. The anagama work (which comprises two-thirds of The Art of Peter Voulkos) demands everything he has to offer—physical strength, improvisational zest, grace and skill—and all that he has learned in 50 years working in clay. “I didn’t have a real feeling about what I could do with the clay until about 15 years ago,” Voulkos says. “Now me and a ball of clay, we’ll get together and it’s perfect. I have that kind of control. I try to dominate it and I let it do its thing too. I almost feel I could take a pile of rough sand and make a pot out of it.”

Now retired from the university, he continues to give demonstrations three or four times a year, and he still works at night. His favorite things remain resistance, confrontation and information. “[If] the material resists too much,” he says, “you’re not in tune with it. You got to feel right about it, you sort of know it’s going to be all right. I’ve gone two, three years without doing anything. I’d walk through the room and feel the clay to see if it was still moist, if it was still alive. If it’s dry, it’s dead. You give it some water, it lives again.”

He talks about a movie he was watching the night before, What’s Eating Gilbert Grape?. “A woman’s husband ran away, and this woman had family, one of the children was slightly retarded. The family adored the little kid. They had to watch him all the time. Because the husband left, the woman began to get fat, she sat in the house and ate and ate, got to be 500 pounds, couldn’t move. Then one day she got up and walked upstairs. They got her into the bed. And she died. The kids always protected her. At the end they decided that the only way to remove her body was to get a crane to get her out. But they didn’t want people to stare at her. So they burned the house down to prevent people finding her. Her spirit was free to fly.”

I ask if he believes in reincarnation. “Someone else asked me that the other day, a Chinese guy,” he says. “Basically I’m an agnostic who believes in a higher power. Who knows? It would be great if you could come back. We’re all built out of the same atoms that were always here. I told him I’ll probably come back as some dumb lawyer. ‘No,’ he said, ‘you’ll come back as something better.’ I live for today; it’s a nice thought, though. In the next life what the hell would that be? Maybe I’ll come back as some big-ass bird.” He grins.

We leave the studio, go in to see Ann. As we pass one of the wood-fired stacks, Voulkos touches it with both hands, one on the belly, one on the neck—a double blessing.

Published in The Museum of California magazine, Summer 1995, in conjunction with The Art of Peter Voulkos at the Oakland Museum of California. The exhibition ran from July 22 through November 12, 1995.