PCVs and Wayuu Blamed for Drug Trade (2019)

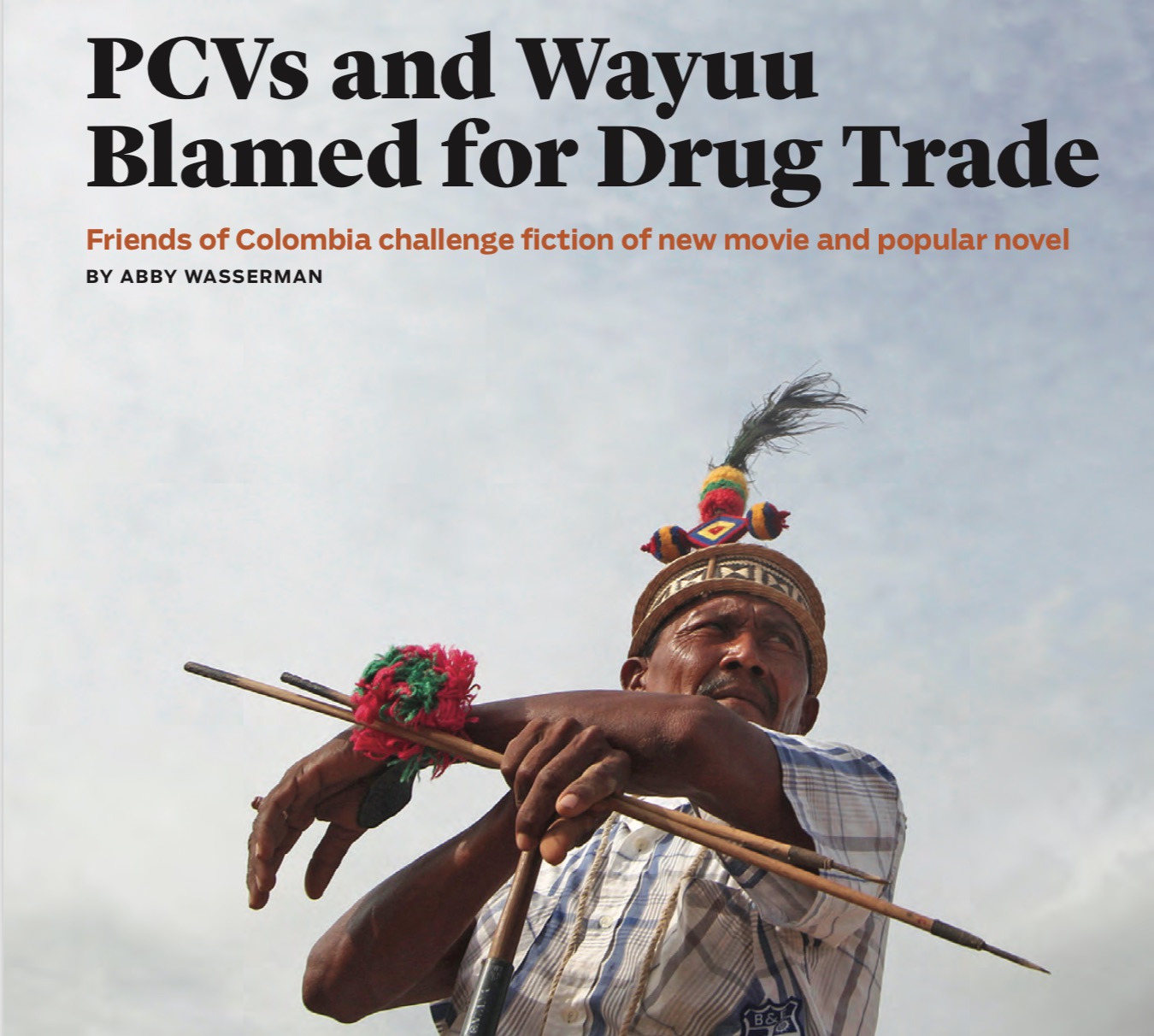

Photo by Joaquin Sarmiento/Reuters

Photo by Joaquin Sarmiento/ReutersIn the 2004 movie El Rey, the mundane life of a Colombian bar owner Pedro Rey is changed when a Peace Corps Volunteer introduces him to the drug trafficking business. In the 2011 novel The Sound of Things Falling, a Peace Corps staffer induces a Colombian pilot to fly marijuana and then cocaine to the United States. The film Birds of Passage, released in 2018, depicts Peace Corps Volunteers in La Guajira, a remote region of Colombia, handing out anti-communist pamphlets, trolling for marijuana, and pioneering the export of weed. These are artistic manifestations from Colombia of a longstanding rumor that Peace Corps Volunteers played a key role in the first days of narco-trafficking in that country.

Rumor-mongering about the Peace Corps has a long history in Colombia. When the first PCVs arrived in Bogotá in 1961, the rumor was that they were CIA. It was the Cold War, and here were Americans who had the capacity to penetrate to the most intimate social fabric of the country. That created fascination and fear, says Colombian historian Lina Britto of Northwestern University, a leading scholar of la marimbera, the marijuana boom on the Caribbean coast of Colombia.

The CIA rumor did not gain currency over time; Peace Corps Volunteers were not spies. They were there to build roads and bridges, dig wells, address health and sanitation conditions, train teachers in the use of the country’s new educational TV programs, assist small farmers to increase their yields, and work side-by-side with juntas of acción communal on self-help projects. In time, they became advocates for the often-disenfranchised communities in which they lived and worked.

But rumor thrives in a vacuum. After 20 years of service to Colombia, Peace Corps pulled out as drugs-related violence escalated in-country. During a nearly 30-year absence, a generation grew to adulthood without direct experience with Peace Corps Volunteers. Some notable politicians pointed blame at the United States for the tragedies narco-trafficking wrought in Colombia and, since the United States was the main market for marijuana, many Colombians came to believe the rumors.

NOT JUST PEACE CORPS

Peace Corps Volunteers are not the only group misrepresented in Birds of Passage, Pájaros de Verano, a movie that claims to be based on true events. The main protagonists of the film are the indigenous Wayuu of La Guajira, a state in the northeast of Colombia that encompasses desert, mountain range, and tropics where I lived for a year and a half as a community development Volunteer in 1964 and 1965. The Wayuu, whose territory is the arid region north of the capital Riohacha, are portrayed as central to the cultivation of marijuana and the main profiteers from its export. But marijuana was actually cultivated in the Sierra Nevada, far from Wayuu territory, and the Wayuu were not the ones who cultivated or profited.

“I lament that such a beautiful movie with incredible cinematography and beautiful symbolism is so sloppy in terms of historical fact,” historian Britto told me in a telephone interview. She says that making the Wayuu the protagonists “is a huge distortion that con- fuses audiences.” The filmmakers, she says, focused the marijuana business on the Wayuu “because they’re colorful. It’s like making a movie about World War II and making the Nazis French [because] their language sounds so much prettier than German.”

She continued, “And they caricature the Peace Corps—it’s laughable. That’s not the way the Peace Corps interacted with people on the ground. They are projecting this mythology we have in Colombia, a narrative we have constructed to excuse ourselves from culpability in this illegal business.”

The film’s co-producer, Cristina Gallego, was three years old when the Peace Corps left Colombia. Speaking in Spanish in a TV interview at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, she said the mission of the “Fuerzas de Paz” was to combat communism, and stated that Peace Corps Volunteers were “instrumental in laying the bases for the drug cartels, later taken advantage of by Carlos Lehder and Pablo Escobar. The Peace Corps saw opportunity in the United States, which wanted marijuana, and the networks were established and later taken over by the cocaine interests.” Her confidence in these erroneous assumptions is breathtaking.

FRIENDS PROTEST

Crippling this rumor within the popular culture of Colombia is a daunting task, but Friends of Colombia, an organization of RPCVs and an NPCA affiliate, has achieved some success with North American media. When Friends of Colombia President Arleen Cheston and board member Ned Chalker attended the 2008 premiere of the National Geographic documentary, Ancient Voices, Modern World: Colombia and the Amazon, they were shocked to hear Colombian sociologist Alfredo Molano claim that Peace Corps Volunteers introduced marijuana into the Sierra Nevada. Cheston had also served in La Guajira, the region in question, and knew the Volunteers. She complained to Wade Davis, an anthropologist who hosted the film and wrote the book of the same name.

“I told Wade Davis that it was impossible,” Cheston says. “I was afraid the allegation would result in negating the positive work Peace Corps had done in Colombia.” Cheston asked another member of the Friends of Colombia board, Jerry Norris, to research the long history of marijuana and coca/cocaine in Colombia. Cheston then contacted the CEO of National Geographic, who complied with her request to delete Molano’s accusation made in Spanish of Peace Corps involvement in the marijuana industry. The documentary’s producers substituted the word “foreigners” for the term “Peace Corps.” Cheston was satisfied.

In the last weeks of 2018, I interviewed Colombian scholars and wrote to Cristina Gallego and the author of The Sound of Things Falling, Juan Gabriel Vásquez, requesting information on their sources. Gallego replied and sent attachments for video clips and studies that she thought proved her point, but only show the power of rumor to persist. Juan Gabriel Vásquez did not respond.

When Gabriel Vásquez spoke about his book at the Miami International Book Fair shortly after its publication, Stanley Boyn- ton was in the audience. Boynton had served in Colombia in the 1960s and returned in 2015 as a Peace Corps Response volunteer in Dibulla, La Guajira.

“Even he admitted that there was no concrete evidence of volunteers engaging in the behavior he described in the novel,” Boynton recalls, “but he said that he cast the role of a PCV in that fashion because it was believed that it had conceivably taken place. In doing so, he tarnished without reason or concrete examples the image of the Peace Corps and the volunteers. He seemed to think that authors are allowed to engage in defamation without penalty.”

FLAWS OF FICTION

Norris’s White Paper identifies serious flaws in both the movie and the novel. A major character is Elaine Fritts, a Peace Corps Volunteer who marries a Colombian, bears a child and continues her service without a hitch. In reality, either the marriage or the birth would be enough to terminate a volunteer. To serve the plot, she remains a Peace Corps Volunteer for several more years. Another character in the novel, Mike Barbieri, is a Peace Corps staffer who deals in drugs with impunity until he ends up dead in a ditch, shot in the head by an unknown assailant. Yet no Peace Corps staffer was ever prosecuted for trafficking drugs, nor were any murdered in Colombia. Fiction is fiction, of course; but incidents that involve real organizations are most believable when based on fact.

The belief that Peace Corps Volunteers bear primary responsibility for instigating narco-trafficking in Colombia goes way back. As historian Britto writes in her forthcoming book, now under the working title of The Marijuana Bonanza: The Rise and Fall of Colombia’s First Drug Paradise, the late José Cervantes Angulo, a journalist for El Tiempo, in 1980 published La Noche de las Luciérnagas (The Night of the Fireflies), a collection of his articles about the early years of the drug trade in Colombia. Based on uncited sources, he reported that “a couple of gringo hippies” had gone into the foothills of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and, finding that the Indians there were cultivating marijuana, took home a large quantity and contacted wholesale dealers in the States.

The “gringo hippies” did not necessarily mean Peace Corps Volunteers until the late Colombian lawyer-diplomat Victor Mos- quera Chaux claimed that they were. In a 1984 op-ed piece for El Espectador newspaper, he alleged that Peace Corps Volunteers were the guilty ones not only for marijuana trafficking but for cocaine. He cited no proof for these blanket accusations.

Like the old parlor game of Telephone, more politicians and ultimately writers and filmmakers repeated this allegation until it became widely believed. It might have made a difference if Peace Corps had been around to refute it by their presence, but they’d left Colombia two years before.

Colombia’s rural marijuana industry turned the nation into a major hub of narco-trafficking. In one day in 2000, a Black Hawk helicopter of the Colombian military destroyed 44 cocaine labs in Norte de Santander province near the Venezuelan border. (photo by Reuters)

Colombia’s rural marijuana industry turned the nation into a major hub of narco-trafficking. In one day in 2000, a Black Hawk helicopter of the Colombian military destroyed 44 cocaine labs in Norte de Santander province near the Venezuelan border. (photo by Reuters)

FINDING LA MARIMBERA’S TRUTH

Friends of Colombia is using research and strategic communication tools to reclaim the truth about la marimbera. The main thrust of research to date has yielded positive results. The historian Britto has rejected Mosquera Chaux’s casual linking of marijuana to cocaine. “Cocaine is a different business,” she said during our interview. “And I haven’t had any evidence of Peace Corps being part of the cocaine trade. It’s true that American buyers came to buy marijuana. Americans did do transportation, but it’s very different to say they were the pioneers and responsible for this business.”

That responsibility rests with Americans such as Allen Long, who moved 972,000 pounds of Santa Marta Gold between Colombia and the United States in his decade-long career. The Virginia native was the most successful marijuana smuggler in America, according to Robert Sabbag, who tells Long’s story in Smokescreen: A True Adventure. Long gave up the smuggling business in 1981, was prosecuted, copped a plea, and spent five years in jail. He died in 2012 in California at the age of 63.

Robert Sabbag has been writing about the illegal drug trade in general and Colombian drug traffic in particular since 1974. He interviewed hundreds of people on both sides of the law and at every level of government over the course of his research for the 1976 book about the cocaine trade, Snowblind, and for Smokescreen.

Sabbag told me in a recent telephone interview, “The assertion that Peace Corps Volunteers were instrumental in the history of drug trafficking is not in harmony with anything I’ve learned in my research and writing about the drug trade in Colombia.

“I have met a lot of Peace Corps Volunteers, and they are some

of the best people I know—dedicated to their work, not to how

they can turn it to their commercial advantage.”

Author Abby Wasserman in Wayuu traditional dress stood, left to right, with Julio, Alvaro Cepeda, and PCV Bill Stowe in Baranquilla. (Photo by Joan Mansfield)

DEVOTED TO COLOMBIA

The conflation of Peace Corps Volunteers and stoned hippies on a beach in a film that blithely co-opts the culture of the Wayuu should not be surprising but it is upsetting to those of us who know better.

After two to three years of Peace Corps service, most of us returned to the States to teach, practice law, work as court translators, become journalists and filmmakers, nurses and social workers, agronomists, and environmentalists. Some stayed on in Colombia. Friends of Colombia never abandoned the country where we’d formed friendships and experienced youthful rites of passage. We initiated and supported educational and community development projects on the Caribbean coast and in the Medellín area. Friends of Colombia provided school materials, uniforms, shoes and tutoring to 35 grade school children through Paso A Paso; funded scholarships for higher education, including university, through The Magdalena Foundation and Fundehumac; brought computer technology and computers to schools in the Medellín area through the Marina Orth Foundation; and implemented micro-loan programs through The Colombia Project to enable women and men to start cottage businesses. These efforts continue today.

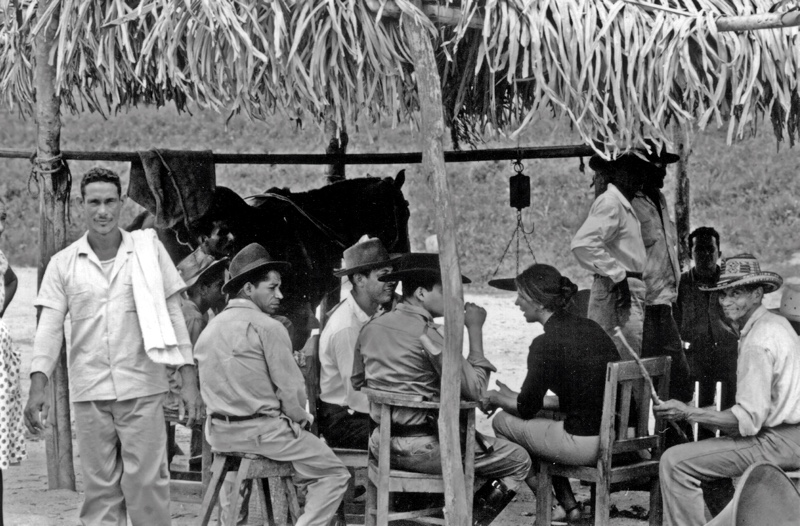

Abby Wasserman with members of Mingeo Junta, 1965. (Photo by Howard Converse)

Abby Wasserman with members of Mingeo Junta, 1965. (Photo by Howard Converse)In 2008, Friends of Colombia organized a conference in Cartagena. Two hundred Returned Peace Corps Volunteers attended, many returning to Colombia for the first time. President Uribe addressed the conference and awarded a Cruz de Plata to Friends of Colombia for their continuing contributions. Colombia had recently mandated the teaching of English to every school child, and soon after that we joined with coffee growers of the Federación Nacional de Cafeteros for a series of workshops in Colombia for English language training. American teachers financed their own travel expenses to provide workshops giving Colombian teachers basic tools for teaching English as a second language. It was another step that led to President Uribe’s formal invitation in 2010 for Peace Corps to return to Colombia.

After our language training workshops, a group of Peace Corps Response Volunteers were sent to Colombia. Their previous Peace Corps experience and their mastery of Spanish meant they would hit the ground running in a variety of self-help projects. They were followed by a new crop of Peace Corps Volunteers. At this writing, some 250 have had assignments in a new era for Peace Corps in Colombia. The individual experiences of Volunteers and the painstaking scholarship of historians may not be as sexy as a well-made film or a bestselling novel, so it’s even more urgent that the truth does emerge.

Are these efforts by Friends of Colombia to counter rumor and refute allegations in the media worth the trouble? There is no doubt in Jerry Norris’s mind that they are.

In his White Paper conclusion, Norris argues that between 1961- 1981 thousands of Peace Corps Volunteers served in Colombia. “The Sound of Things Falling and its acceptance by... media groups as the foundational basis for the initiation of the modern drug trade between that country and the United States profoundly discredits each of them for their service to a place many of them consider their second home. If Friends of Colombia doesn’t stand up to refute the uncorroborated assertions made in films and a novel, then comments like this... from National Public Radio: ‘[The novel] shows “Peace Corps hippies who peddle drugs”... will stand as a marker on [our] time in Colombia.’”

And that would be simply unacceptable.

Abby Wasserman is a journalist, magazine editor and former editor of the Friends of Colombia newsletter. She has written for the Washington Star, Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle, Sonoma Magazine, and has published five books. She is editor of the Mill Valley Historical Review.

Originally published in National Peace Corps Association magazine "Worldview" Spring 2019.

Photo credits:

- Photo by Joaquin Sarmiento/Reuters

- Colombia’s rural marijuana industry turned the nation into a major hub of narco-trafficking. In one day in 2000, a Black Hawk helicopter of the Colombian military destroyed 44 cocaine labs in Norte de Santander province near the Venezuelan border. (photo by Reuters)

- Author Abby Wasserman in Wayuu traditional dress stood, left to right, with Julio, Alvaro Cepeda, and PCV Bill Stowe in Baranquilla. (Photo by Joan Mansfield)

- Abby Wasserman with members of Mingeo Junta, 1965. (Photo by Howard Converse)