Passing Between Worlds: The Art of Fred Martin (2003)

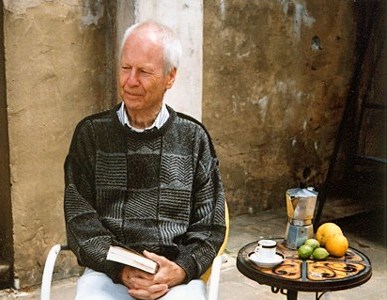

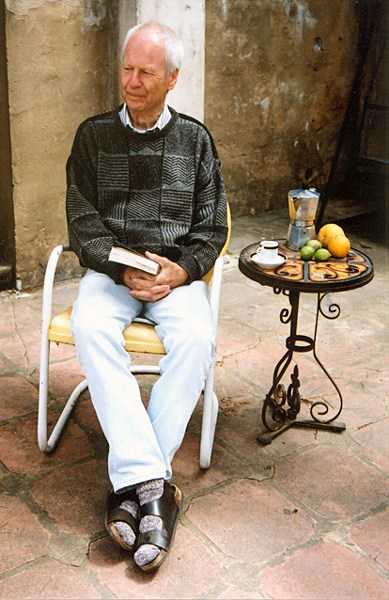

Photograph of Fred Martin at his Oakland home by Abby Wasserman, 2003.

Passing Between Worlds: The Art of Fred Martin (2003)

by Abby Wasserman

In 1967 Fred Martin noted in his studio journal, "You can work from the world within, you can work from the world without. But to work from the free passing between worlds, that is the difficulty."

Art for Fred Martin is a powerful force for understanding and change. He once wrote that his art "shows the tasks of my life at the times when I must undertake their work" in almost a mystical way. In other words, art is not separated from life; it is life. Art also can be a sign post pointing direction, a mirror trained on the self, a healing force in the world, and a hedge against loss. Martin's work often engages the viewer, according to Oakland Museum of California Chief Curator of Art Philip Linhares, in the indefinable place "where words don't count and music doesn't sound."

On a warm spring day in 2003, Fred Martin answers the door of his Oakland home in a crew neck sweater, faded grape-colored button-down cotton shirt, and faded blue jeans. It's a collegiate look, which works well, for he is as slim as many a youth. He has clear, very intense blue eyes, pale brows and lashes, healthy pink skin, straight teeth, and laugh lines reaching from his eyes to his chin. His grey hair is softly spiky. He keeps his considerable energy contained and speaks calmly and reflectively, giving the impression of a sage with a sense of humor. "I always imagine Fred wandering through the hills of Greece or Italy in a toga," Linhares says. "He appreciates the landscape and savors the change of seasons. There's a simple profundity about his work. It's here and now, but archetypal, crowded with symbols."

Martin seems to have lived more than one life. He is a prolific painter, one of the most prolific around, according to Linhares, who looked through thousands of works in the studio to select 137 for a retrospective at the Oakland Museum. Martin is Dean Emeritus of the San Francisco Art Institute and an art writer. Since 1995 he has been a visiting professor in the Arts and Consciousness Program at John F. Kennedy University in Orinda, Calif. He is a frequent guest lecturer in the U.S. and Canada on topics having to do with the interface of art and spirituality--art and consciousness, archetypal images, art and healing, and the relation of art to spirit and art to alchemy. His classes on drawing and art history this year incorporate major religious traditions and shamanism, Jung, Munch, and Kandinsky, "to set students' work in context and to find friends out there in the world."

In 2002 Saybrook University, an international school of psychology based in San Francisco, presented a seminar on Martin subtitled "Soul and Spirit in a Creative Artist's Work." In announcing the seminar, Saybrook described Martin's paintings as "consistently rich with information about the artist's sense of himself, his spiritual resources, and his relationship to his materials . . . [his] mastery of abstract form and color combines with his intuitive and divinatory creative method to produce his own very personal, and still evolving, style of painting."

Martin's life is an examined one, as every philosopher's should be--and it is also a richly expressed one, which accounts for the well-being he exudes on the spring day we meet.

Many artists shrink from revealing too much about themselves in their art, even though the creative act is expressive of self by its very nature. Martin does not shrink. He is curious and analytical. He has kept a studio journal for decades, and has published books on his ideas about art. He acknowledges that this path is not always smooth, that his revelations might conceivably interfere with others' spontaneous views of his work, but it's the path he has chosen. He cites Mark Rothko, with whom he briefly studied at the Art Institute, as one who left the meaning and truth of his work mysterious. But Martin's choice is "to know and show and tell it here."

Working full-time when he and his first wife, Jean, were raising their children Demian, Fredricka, and Anthony, Martin still managed to paint nights and weekends. In the early 1950s, a few years after his marriage, he had a show and sold paintings for 50 cents each. He writes, "I would rather have had the money than take the paintings home after the show, and I knew there would always be more paintings. I thought of myself in those days as a spawning salmon. Only by scattering millions of eggs across the world could I survive in the few that might remain after my death. I still think that." Such sexual imagery is a recurring theme in Martin's art and conversation; he believes the sexual and spiritual are essential for wholeness.

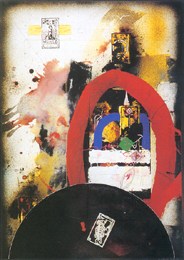

Untitled 1983 by Fred Martin

In 1945 Fred Martin was inducted into the field that would become his calling. He entered the University of California, Berkeley, in design but soon switched to art. His early teachers would become intensely influential, although at first he resisted some of them.

"I was an 18-year-old, pretty hot stuff, just getting involved in modern art," he says. "The first art class I had was with Erle Loran, who taught based on Cezanne's composition. I thought he was an old fool and he thought I was a young brat. He got into visual structure, teaching what amounted to abstract art. Everyone everywhere else was teaching how to draw the figure, but the art department at UCB had no figure drawing class until my senior year. Now I find myself as old and fuddy-duddy as Erle was. I teach much of what he did.

"Margaret O'Hagan taught color by making us buy every pigment of watercolor there was and painting sheets with one color per sheet, then seeing what other colors did on the ground. Looking and experiencing. We barely learned the terms 'hue,' 'value,' 'intensity.' No color wheel. We just looked. She was really tough and she was a woman. I thought, 'Art is not effeminate after all. I can be an artist.'

"Henry Shaeffer Zimmern taught me to 'see the whole thing' as big as an ocean if that's how big it is. Glenn Wessels taught the Cubist analysis of form and that there are not one but many aesthetics. Go looking across the world and its history for whatever has meaning for you, and make the synthesis for yourself."

After receiving his B.A. in 1949, Martin continued at Cal for his secondary teaching credential and master's degree. He joined the Oakland Art Museum as registrar in 1954, staying four years. He painted constantly, won prizes in juried exhibitions, and concurrently began his teaching career on the faculty of the California School of Fine Arts (now the S.F. Art Institute). He served as gallery director and was appointed director of the college in 1965.

Martin proved to be a gifted teacher. He taught art history by lecturing on the life of a single artist in each class, a biographical approach rather than an analysis of styles and movements. These were real lives that his students, if they decided to pursue an art career, could learn from.

"Artists up to the 19th century were craftsmen," he points out. "They had patrons, worked for hire. Art was a job. Then we became romantic and moved into garrets. Our challenge is to get out of the solitary genius mode. I grew up in that mode. Here we have a school with 700 students. They can't all be solitary geniuses. What are we doing to prepare them?"

When he taught a studio painting or drawing course he refused when invited to interpret his students' work, calling on them to decide what it meant. The artist must know the meaning of his own work--that is what matters.

Born in 1927 in San Francisco, raised in Alameda, Martin moved to Oakland in the 1930s. His house, Green Gates, was built in the Arts and Crafts style by Oakland landscape architect and businessman Arthur Cobbledick (who also designed the Oakland Municipal Rose Garden). It was remodeled in the 1920s as an Italianate villa with arches and trellises and patios. Balconies and French doors gather in light. There are carved stone figures on marble columns, a Della Robbia relief of the Virgin Mary, and a brilliant clump of red-violet bougainvillea on one wall. Greenery everywhere: lawn, yew trees, redwoods, and a magnificent fig tree. Most of the wrought iron fences and gates are painted bright blue, evoking the Mediterranean.

Stephanie Dudek, Martin's wife since 1992, offers Earl Gray tea and a plate of cookies. She is a psychologist and professor at the University of Montreal. Her husband looks admiringly at her. They've been married 10 years and it's clear that romance has not gone south. They maintain two houses, in Oakland and Montreal, traveling back and forth with their blended family of dogs--her one, his two. On this spring afternoon, the dogs roil underfoot, claws skidding on the parquet floor, emitting strangled barks. Martin exiles them briefly, but it's clear that as far as dogs go, he's a pussycat.

The house reflects a voluptuous spirit. It's lushly furnished with books, art and decorative objects from Martin's travels. The library, his office, looks out to a long rectangular lily pond. He likes to sit and read by the pond while drinking espresso. The detached studio, only steps from the house, reflects another side of the artist, one that's compact, spare and utilitarian. Everything in the studio is neatly ordered--the paper, acrylics and brushes in their places like musical instruments or the utensils of a master chef.

For 10 years, 1965-1975, Martin and his colleague Alice Erskine, director of student services, ran the Art Institute. It was a halcyon time. Enrollment increased to more than a thousand students. Martin relished his leadership role and administration interested him tremendously. He was also showing and selling his art, with gallery representation on both coasts, but not many students at the Art Institute were aware of it.

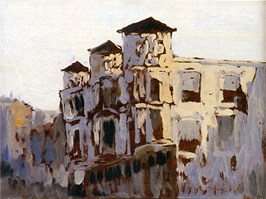

Golden Gate at Laguna by Fred Martin

"He didn't thrust it forward, that's not his way," Phil Linhares says. "People were renting studios for two or three cents a square foot. Artists were working large, and some very splashy work was going on at the time. Fred's work often consisted of quiet, very literary collages. He was director and didn't want to impose himself on the scene, because he did have a dominant position, and the Art Institute was the center of activity in the Bay Area then, more than the University of California or San Francisco State or CCAC. There were a lot of prominent teachers. Fred was behind the curtain manipulating the scene, bringing in visiting artists such as Bruce Nauman and H.C. Westermann, the Chicago sculptor. He was orchestrating that. It takes incredible discipline. Fred had the subtlety and the good sense not to push his own work forward at the school."

Alice Erskine recalls, "Fred was always wonderful with people. He got along with everybody. He got things settled amicably. He's a very disciplined person actually; he has certain things he thinks ought to be done and does them. He has a terrific memory of everything you've said and done and have forgotten.

"We would cover every possible approach to a subject, be very sympathetic about the drive behind the art taking place. To him people are very important. I think that was why he was such a good director. Each student was very important to him as a person. The rules didn't count as much as the people making or breaking them."

"At SFAI we kind of make classes up," Martin tells me. "It's better to make them up. I had an English professor who said, 'Remember, TEACH is a transitive verb--I teach this to you.' Information and assignments are thought through, so if you make a mistake you know what it is. It doesn't hurt your soul; it's only a mistake. Correct it!

"The students learn how to look. I try to set it up so if they look clearly, they can draw. Not to draw things, but to learn the principles of visual organization. Drawing is not depiction. It's not making a picture of stuff--not in my course."

Martin's situation at the Art Institute changed abruptly in 1975, when the board of directors hired as president a man he disliked and refused to work under. He gave notice, staying on for the transition, and although the new appointment did not last (the students held a tuition strike and the appointee was let go), Martin still left, disillusioned. He decided to work exclusively on his art, but a habit of part-time painting nights and weekends was hard to break. He took teaching jobs at U.C. Berkeley, San Jose State and other schools. Then, in 1983, his wife Jean was diagnosed with cancer.

When he realized she was ill, Martin tried to make an art for healing, creating the image of a journey through death to life to create health. He turned to archetypes and to the Tarot to help him explore ancient meanings. But his wife didn't get well, and he later wrote that he was faced with the fact that what he had intended to be a proactive art was merely representation: "the picture of my desperation to save her."

In deep mourning, he returned to the Art Institute as dean. His term would last nine more years. Perhaps the job saved him, but he remembers it as a dark period. His attitude towards his art shifted. He had been ambitious; now he stopped caring about selling or exhibiting. Life became for him "an arch wherein each piece of my work was a stone, and to sell or lose a work would so weaken the arch as to threaten its collapse." He felt he could not bear another loss, although he knew loss was "inevitable and absolute for all people and all things." He wrote, "Vincent Van Gogh said, 'What does it matter if a man . . . dies, because another rises in the same place.' Yes, another does rise, but he is not me."

In 1992, he met and married Stephanie. "The roar of life came back in me," he wrote. "I began to paint big once more, the biggest I have ever made, 126 x 126 inches, now in acrylic . . . rather than watercolor because I had to have the tactility of flesh. I made an enormous painting of my sexuality, another of mind and body, earth and heaven, where I could stand and be in the wholeness and shining of the world."

The duality most striking in Martin--visceral/passionate and reflective/spiritual--creates an intriguing balance in his art.

About 10 percent of the work in the Oakland Museum of California retrospective was drawn from a major gift of art he made to the museum. Other pieces are from private collections and from his file drawers. Some of the work has never been exhibited. Included are small cityscapes he painted while sitting in his 1938 Lincoln Zephyr coupe using the steering wheel as an easel. There are collages and drawings; small paintings of imagined faraway places made before he ever left California; large canvases with harvest themes; still lifes and tall narrow pastel works on prepared Masonite; and large works on paper with text and collage elements.

Fred Martin has experimented with many techniques, but consistent in his art are the elegant gesture, the provocative balance of light and dark, the vivid gashes of color, the evident pleasure of exploration, the free expression of emotion, and the intense inclusion of words. His art does indeed suggest a "free passing between worlds" of image and text, mind, body, and spirit.

Images from top:

- Photograph of Fred Martin at his Oakland home by Abby Wasserman, 2003.

- Untitled, July 24, 1983. Collection of the artist. Watercolor with collage, 40 x 30 in. Martin made this powerful image when his first wife, Jean, was mortally ill with cancer.

- Golden Gate at Laguna by Fred Martin, 1957-58, oil on masonite. Collection of the Oakland Museum of California.

© 2003-2005 Abby Wasserman. Originally published under the title "The Art and Lives of Fred Martin" in The Museum of California magazine, Oakland Museum of California, Summer 2003.

Fred Martin's web site is www.fredmartin.net.