Into the Light: The Transformation of Joan Brown (1998)

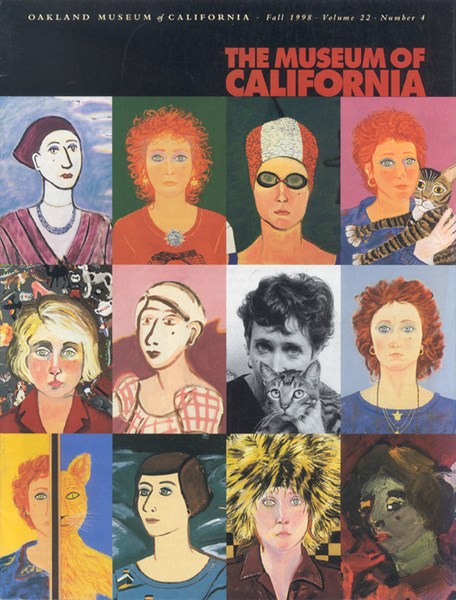

Cover of The Museum of California magazine, Fall 1998, showing details of Joan Brown self-portraits spanning her 35 year career. In center right, detail of a photograph of the artist by M. Lee Fatherree.

Into the Light: The Transformation of Joan Brown (1998)

by Abby Wasserman

Perhaps the best time to die is when one is walking in a state of grace. Those moments are rare, often fleeting, but when they do occur, glorious. The painter Joan Brown died in an accident in India at such a moment of grace, when she was happy, at peace, and doing what she wanted to do--installing an obelisk of her design at the ashram of her Indian spiritual guru.

Yet she was only 52, vitally alive, and the accident was freakish: a turret in the ashram's new museum, then under construction, fell on her and her two American assistants as they worked. She could have left the installation to others but was determined to do it herself. This was entirely characteristic.

The accident affected the lives of three families and many friends and cut short an extraordinary career. The exhibition Transformation: The Art of Joan Brown, co-organized by the Oakland Museum of California and the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum, shows the breadth and quality of Joan Brown's accomplishments. One hundred and twenty-six of her paintings and sculptures are featured. Seeing them, one comes to know her, for Joan Brown's work is largely autobiographical, a "visual diary" reflecting events of her life, people she loved, and things in which she delighted. Above all, they trace her lifelong quest for personal identity and spiritual understanding, and the evolution of her style.

The emotive, unbridled energy of early paintings evolved into an increasing emotional detachment--built-up surfaces flattened out and forms became more precise and decorative. But some attributes stayed constant: her brilliant use of color and the presence of the figure. She came out of art school able to synthesize the figurative and the abstract, but it was the figurative that commanded her interest and dominated her art.

Because her work is often distilled to essentials, her "visual diary" might at first appear easy to read, but there is much hidden under the surface. Brown, after all is said and done, has written in a code known only to her.

Oakland Museum Senior Curator Karen Tsujimoto, co-curator of the exhibition, delves deeply into Brown's life and work in her excellent essay in the book accompanying the exhibition. A second intriguing essay, by her co-curator Jacquelynn Baas, director of the U.C. Berkeley Art Museum, examines symbolism in Brown's work.

Feisty and driven, with a great zest for life, Joan Brown determined to do it all--be an artist, have a career, be a wife and mother. She married four times. Three of her husbands were artists--Bill H. Brown, whose name she kept, Manuel Neri and Gordon Cook. Her fourth husband, Michael Hebel, a lawyer and police officer, shared her spiritual interests and love of travel. Full of contradictions, Brown was direct and open but also hidden and controlled.

Her friend Wally Hedrick believes she was two people. "There was the innocent child, sort of flowing through time, and there was the mature artist, and they just happened to be in the same body at different times." Although small and slight, she swam long distance races in San Francisco Bay. She was a fighter for rights of women without calling herself a feminist. Raised in a troubled family with limited cultural interest, she became a world traveler, embracing the history and cultures of Italy, Mexico, China, Egypt, India--yet living all but three years of her life in San Francisco, her home town. Her vision of possibilities deepened as the years passed.

She was born Joan Vivien Beatty in 1938. Her childhood was a study in chiaroscuro. Raised in the open spaces and brilliant light of San Francisco's Marina, she shared a small rather dark apartment with her parents and maternal grandmother, and never had a room of her own. Her grandmother was unwell; her father, whom she adored, drank heavily each night; and her mother occasionally threatened to jump off the Golden Gate Bridge.

Creating her own world, Brown played with an elaborate dollhouse and made paper dolls, imagining interesting lives for them. The only thing she recalled enjoying with her mother, she told Paul Karlstrom of the Archives of California Art, was dining out at elegant restaurants. Her mother disliked cooking anything but desserts, and sometimes made three for a single meal.

As a child Brown felt no inclination to be an artist. She was an indifferent student but frequented the public library, reading as many as 15 books a week, many on ancient civilizations. As a teenager she spent time after school shopping with her liberal clothes allowance, working to earn her own money, and swimming at Aquatic Park. She liked to draw pictures from movie magazines of film stars like Betty Grable and Arlene Dahl, and vaguely imagined a career in business or fashion. The film star drawings were her portfolio when she applied to art school.

She was set to matriculate at a Catholic women's college when she saw an ad for the California School of Fine Arts. She hiked up Russian Hill to the school and changed the course of her life--it was that simple. CSFA, which later became the San Francisco Art Institute, was different than any atmosphere she had known, and she loved it. Students wearing sandals played bongos in the courtyard, and there were the smells of paint and freedom in the air.

In the late 1950s the two dominant painting styles at CSFA were the "fig" and the "creepy crawly," slang for "figurative" and "abstract." Elmer Bischoff was the leading exponent of the figurative, Frank Lobdell the leading abstractionist. Brown started with design courses but did poorly and almost withdrew. But she had fallen for a handsome painter, Bill Brown, and stuck around to take a landscape painting course in the summer. The course was taught by Bischoff, who saw potential in her work and that gave her confidence to continue. She never looked back; and it was never easy. "It's like pulling teeth a portion of the time, I have to totally pull stuff out," she told Paul Karlstrom. "So I worked like hell that first year, just went on hundred percent into it."

There is a big oil by Brown from 1959 called "Fussing Around by the Light of the Moon." Painted with her sure, energetic hand, it features a couple of abstract objects floating in a seaweed-colored sky. They could be an origami rooster and a wrapped stone. "Fussing Around" is an abstract longing to be figurative. Brown was only 20 when she painted it, and it's so amusing, charming and devil-may-care that it makes one smile. At the same time, it's masterfully controlled, like the taut engineering under the lid of a piano.

"She knew exactly what she was going to do--make art--and nobody was going to stand in her way," sculptor Manuel Neri recalls about Brown, who he would marry a few years later. Part of her intent was academic; she liked the atmosphere at CSFA and stayed to earn B.A. and M.A. degrees and teach classes. Later she joined the art faculty at the University of California, Berkeley, where she was a tenured professor. She believed that everyone is creative.

"She would always say that anyone could do what she was doing if they had the will, the focus and the intent, and were willing to bring out the richness of their inner life," Mike Hebel says. "No one may like it, you may not like it yourself, but it's your work, and if you're going to be an artist, you have to be committed to your work whether anybody likes it."

"The first time I heard about Joan," Wally Hedrick told me, "Elmer Bischoff said to me, 'I have this extraordinary student. She's either a genius or very simple.'"

Her simplicity was fearlessness and disarming directness; her genius was to absorb everything, synthesize disparate styles and create one for herself that was unique and personal. The principles that Bischoff taught his students and which informed Brown's life as an artist were to work hard, "follow your nose," respect the validity of your own imagery, take chances, and accept the struggle of the creative process regardless of rewards.

"Elmer was able to talk to you very deeply about painting, which I think is very mysterious," Bischoff's wife, painter Adelie Landis, says. "I don't know many people who can do that today. He would pick up in the painting what you were trying to do and weren't able to express, and where you should go. And for an artist, that's a road ticket to freedom and realization. It was like, whoa!"

The art school was at the center of a creative, free-wheeling group of men and women who worked and partied hard. Manuel Neri says the art market at that time was so depressed in San Francisco that no one expected to sell, and this allowed them to enjoy the freedom to go where "their noses" led them. The first place Joan Brown showed outside SFAI was the 6 Gallery, started by a group from the school that included Wally Hedrick. The 6 was where Allen Ginsberg gave the first reading of his poem Howl, signaling the start of the Beat era.

Hedrick and his wife, Jay DeFeo, lived next door to the Browns on Fillmore Street. The couples were so intimate that they punched a big hole in the wall so they could step into each other's studios. DeFeo and Brown enjoyed a lively rapport. A few years older, DeFeo had known from an early age that she would be a painter, and she had a lot to teach Brown. In the Fillmore apartment, DeFeo created her tour de force, "The Rose," now owned by the Whitney Museum of American Art. New York dealer George Staempfli stepped through the hole between the studios and bought paintings by Joan Brown, the first she'd sold, and let her fill in the amount on the check.

Brown was insatiable in her appetite for learning, Hedrick recalls. "She would call me up in the middle of the night and say, 'What is this stuff that Leonardo discovered?' I'd say, 'What do you mean, what are you talking about?' She'd say, 'Perspective.'

"'Well, Joan, perspective is how the camera sees.' I'd try to give her a simple answer and she'd demand"--his eyebrows shoot up--"she'd demand, 'You've got to come over tomorrow and teach me perspective.' Well, I mean--to me, perspective is so obvious, why do I have to teach anybody? Well, for Joan it was not obvious. She saw things flat. I mean the idea of things getting smaller as they go away had never occurred to her."

In the 1970s, adopting her preferred way of seeing, Brown would paint flat planes in which the play of shapes, light and color, not perspective, dominated. Many of these paintings call to mind the cut-paper work Matisse did in the late 1940s: celebrations of pure color and playful inventiveness of shape.

Less than two years after entering CSFA, she was showing in galleries in the Bay Area and Staempfli gave her a two-person New York show. She was 22. This brought media attention, more shows, more success, and for awhile it all went to her head.

"Early on, when I met her, she was like a young--if a rooster can be female, she was like a rooster," Adelie Landis says.

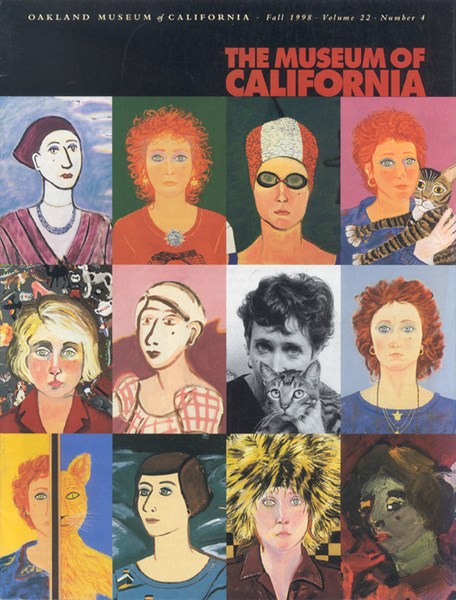

Portrait of Lupe by Joan Brown

There was high, fast living for a few years, but then she settled down, because work, not fame and fortune, was the most important thing to her.

"Most artists, after they get out of the protection of the school, have real difficulty in sustaining even a tremendous talent," says Wanda Hansen, who with Diana Fuller was Brown's San Francisco dealer for years. "You have to have a discipline and a commitment that excludes everything else. Art is your primary purpose in life. She had that. She had the formula that makes a great creative artist. Integrity with the work, dedication, an obsessiveness. She had tremendous stamina and could just focus." Fellow artists recognized this, encouraging her and speaking enthusiastically and generously about her work.

Joan and Bill Brown were married only a few years but remained friends until her death. Her next marriage, to Manuel Neri, lasted four years and produced Brown's only child, Noel. She was not going to repeat her parents' stoicism in the face of unhappiness. Manuel Neri says the only time they got along was in the studio, where they shared extraordinary rapport and trust.

Karen Tsujimoto writes about the synergy between them; artistic synergy seems to have been an essential element in Brown's first three marriages.

Brown featured her husband in paintings, including "Family Portrait" (1960), which is a picture of a sober (very sober) conventional couple, something they were not in real life, sitting with their dog. Brown liked this painting and considered it her most personal at the time; still, she sold it through Staempfli. The woman in the portrait looks less like the gamine she was in her youth than her mother. Bob, the handsome bull terrier who appears in "Family Portrait," became unpredictable, biting Neri "once weekly" and in a terrible incident, attacking and killing the dog next door. "It was like having a mean child," Neri says, indulgent even now.

A different view of a relationship surfaces in "The Day Before the Wedding" (1962), in which a naked woman appears in fearful flight from some dark fate. "The Bride" (1970) imparts yet another take on marriage. Painted while Brown was married to Gordon Cook, it depicts a cat "bride" in a white frock standing erect and proud, holding a bouquet in one paw and a leash in the other, with a huge rat on the end of it. Colored fish swim across a watery blue sky. The ground blooms with poppies. Brown loved dogs and cats equally, but cats symbolize the feminine, indeed Brown herself, in many of her paintings. In "The Bride," the upright, ladylike cat clearly keeps the lurking rat (the groom?) in place. There are plenty of fish in the sea and it's springtime under her feet. "The Bride" exudes well-being and pride in the ability to keep emotions (and marriages) under control.

The most important male in Joan Brown's life was her son, Noel. She once confided to Wanda Hansen, "I'm crazy about him." She painted at home to be near him, and painted him in many settings--the kitchen, on his first pony ride, dressed in a Halloween costume.

Now 36, Noel Neri lives on the east coast and is a sculptor. He has Frida Kahlo eyebrows and a quiet, warm, self-contained manner. He remembers the costume his mother made when he was two, immortalized in "Noel on Halloween" (c. 1964): his friend, the son of Bruce and Jean Conner, also had a homemade costume that Halloween. "I was dressed as a tiger and he was dressed as a lion," Noel recalls. "His mother could sew really well. It was a beautiful lion with a huge mane and his face stuck out. It was a pretty wonderful costume. And mine was really funky. It was more an object of art than it was a Halloween costume. I think that's why she had a lot of fun doing it." "Noel on Halloween" depicts the little boy in a costume more spotted jaguar than tiger, with whiskers painted on his face. Surrounded by thick red paint, with a white bird in his hand, the child is the picture of sturdy innocence. Brown's paintings of Noel are tender and happy, as though she is experiencing childhood's magic with him. She encouraged his artistic tendencies, pinning up his pictures in her studio. He says she always asked him what he thought of her paintings and listened happily to his comments.

During her marriage to Gordon Cook, Brown continued to paint prolifically, including lively, often mysterious images of lovers, dancers and swimmers. The couple loved dancing and distance swimming in San Francisco Bay. It was an odd pairing: she was outgoing and optimistic, he was introverted and critical and, according to friends, sometimes cutting toward her in public.

But the marriage lasted a decade, and Adelie Landis saw a softness surface in Brown that she hadn't seen before. She lost some of her edge, Landis says, and became warmer, less distant, which may have reflected a warming generally towards other women. Her hostile, depressed mother had committed suicide in 1969, and Brown felt literally able to breathe easier, she told Karlstrom, as though a weight had been lifted from her.

Brown's paintings from the years of her marriage to Cook are disciplined and spare. "Austere" and "spare" are words that apply to Cook's small canvases; but the subject matter and feeling tone of the artists and their techniques were markedly different. There was, once more, a synergy in their union as artists. Cook had been a printmaker and she helped him become a painter; Brown's paintings came increasingly to resemble prints--flat and decorative, with meticulous graphic attention to form, color and composition.

Brown's willingness to test herself in the turbulent, frigid waters of the bay is hard to understand except by others who do it. Her swimming coach, Charlie Sava, was an important mentor, teaching her to distill to the essentials, as was her friend Modesto Lanzone, a Dolphin Club member who rowed beside her during arduous swims and helped her overcome her fears. "Everyone said she was too skinny to do it, and she was intimidated," Lanzone says. "But she was a fighter." Swimming became extremely important to her. For Lanzone as well as Brown, "water was a mental therapy." It's tempting to compare Brown's determination to stay afloat in the bay with her mother's threats to kill herself by jumping off the bridge. Swimming required a tremendous act of will, and perhaps more than any other challenge, built Brown's trust in herself.

Her 1976 self-portrait, "After the Alcatraz Swim #3," records a swim during which she became disoriented and exhausted. Yet in the painting she sits neatly dressed, expressionless and composed in front of a painting of the bay, a tumult of waves in which swimmers and boats are tossed. Alcatraz Island and its prison building are silhouetted in the background. In this painting Brown comes to terms with the dualities of risk and security, life and death, imprisonment of the body (helplessness) and freedom of the mind. The work also indicates how tightly in control she kept her turbulent emotions. This Alcatraz swim, which she was to do twice more, was a profound experience from which she emerged stronger while coming to terms with her own frailties.

Her paintings of dancers are festive but with an edge of melancholy and occasionally the macabre. In "The Last Dance" (1972), a rat devours a dancer while others blithely walk on. In "Dancers in a City #2" (1972), she paints a woman dancing with an invisible man. Brown often painted men in shadow or dissolving, as though she couldn't quite believe they would always be there for her. The floor in "Dancers" is orange, the cityscape purple, and some sort of big dog stares intently at the viewer.

One of Brown's most romantic paintings is "The Kiss" (1976), painted after a trip to Italy with Modesto Lanzone. Based on the famous Rodin sculpture in Paris, and an embracing couple she observed on a park bench, "The Kiss" is a passionate, exuberant work dominated by deep red, a color Brown loved and used to great effect. The fluidity of the embracing couple and landscape contrast with the stiff embrace of "Dancers in a City."

In 1979, in keeping with her desire for spiritual community, Joan Brown began attending meetings at Ananda Community House in San Francisco, an offshoot of the Self-Realization Fellowship in southern California. There she met Michael Hebel. On the day of their wedding on May 11, 1980--a Hindu ceremony at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art attended by artists, art world denizens, police officers and lawyers--Brown joked, "Your friends aren't going to arrest my friends, are they?"

Theirs was a happy match with a core of affection and good will. "I was a good balance for her because she had a bucketful of tenacity and a thimbleful of patience," Hebel says. "I have a bucketful of patience and a thimbleful of tenacity."

Hebel moved into Brown's house on Cameo Way in San Francisco, which she had previously shared with her son and Gordon Cook. In a subtle way, this house recalled the home of her childhood. "There was something ingrown about it," Adelie Landis says. "It retracted in upon itself."

With an architect, Brown and Hebel remodeled the house to suit them both. A dark upper floor was turned into a light, open library and small meditation room, with glass doors leading into a rooftop solarium, where Brown placed a little mosaic fountain of her design. They also enlarged the dining room on the closed-in first floor, putting in a stone fireplace and bringing in light through a high window.

Long fascinated with the quality of light in paintings by Rembrandt and Velasquez, she began to work on capturing light "shimmering from within" in her paintings, rather than applied from without. Brown was moving closer to the light she desired, a lightness of spirit. She and Hebel traveled several times a year, to Mexico, Italy, China and India, and she continued to paint prolifically. Always interested in public art, she completed a series of large obelisks for installation in public places. The ancient obelisk form intrigued and inspired her. Although three-dimensional, the surfaces of an obelisk are flat, so it bears some relation to a painting.

Her subject matter during the last decade of her life dealt increasingly with her spiritual beliefs and devotion to an Indian guru, Sathya Sai Baba, whom she and Hebel first encountered during their honeymoon in India. In addition, after rejecting Catholicism in her youth, Brown now returned to it through the teachings of St. Francis of Assisi, for whom she felt deep affinity, in part because of his compassion for animals. During this time her use of symbols became less personal and idiosyncratic and increasingly conscious and studied. Some of her "metaphysical" paintings appear to be visual conversations in which she seeks to understand and appreciate Sai Baba's metaphors.

Noel Neri

Noel Neri became a father in the mid-1980s, and Brown's tender portrait of her grandson fuses the personal and spiritual. "Portrait of Oliver Neri" (1988) is a portrait of a child and an inner self-portrait (the child signifying Brown's own innocence and openness), a grandmother's blessing, and an affirmation of faith. The little boy in bright overalls floats in a deep blue sky (the unlimited horizon of the soul) swept by dawn's rosy, glowing clouds. He wears two necklaces--one with a portrait of Sai Baba and the other a yin-yang--and holds a small lotus flower, symbol of spirituality, creation, knowledge and compassion. A jaguar and a deer rest at his feet, indicating a peaceable kingdom Brown believed was approaching.

In September 1990, Joan Brown and Noel Neri left California to install one of her obelisks in the new Eternal Heritage Museum at Sai Baba's ashram in India. The project was delayed, and Noel left after some weeks to return to California. On October 26, an improperly anchored turret in the museum fell, killing Brown and her assistants, Lynn Mainric and Michael Oliver, and destroying the obelisk. Her body was cremated at once and her ashes scattered into the Ganges, with none of her family present.

With no hope of knowing the exact circumstances of the tragedy, her family sought ways to come to terms with their loss. They were comforted by knowing how happy Brown had been, how sure of the signposts marking the progress of her inner journey.

"Before I left, when we said goodbye, I realized that her life had changed," Noel Neri says. "She was living a spiritual life and our relationship was going to change, her relationship with her husband was going to change. I felt she couldn't end her life in a better time. So many people are sad and bitter when they die. I think she had a very glorious end."

In Joan Brown's last years she was moving towards a synthesis of universal and personal symbols, just as she had earlier synthesized the abstract and figurative. Art, intuition, and trust in the commonality of human experience were her pathways to the light of understanding. She graced the world with more fine work than many artists of great longevity leave behind. But we'll never know where, or how far, she might have traveled next.

Images from top:

- Cover of The Museum of California magazine, Fall 1998, showing details of Joan Brown self-portraits spanning her 35 year career. In center right, detail of a photograph of the artist by M. Lee Fatherree.

- Portrait of Lupe by Joan Brown, 1962. Oil on canvas, 30.125 x 25.25 in. Collection of the Oakland Museum of California, gift of Noel Neri. Photographed by M. Lee Fatherree.

- Joan Brown's son, Noel Neri, photographed in 1998 by Abby Wasserman.

Originally published in The Museum of California magazine.

No reproduction without express written permission of the Oakland Museum of California.