Frank Day: Memory and Imagination (1997)

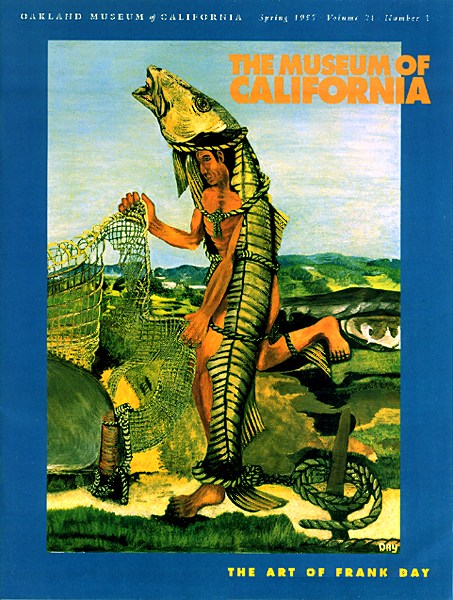

Cover of The Museum of California magazine, Spring 1997, with Frank Day's "Fish Dancer," ca. 1973-75, oil on plywood, 24 x 17 in. Collection of M. Leigh and Sandra W. Marymor. Photographed by M. Lee Fatherree.

Frank Day: Memory and Imagination (1997)

by Abby WassermanMemory and imagination inform creative work. Imagination constantly dips into wells of memory for inspiration, and memory calls on imagination to interpret experiences we only half-understand.

The paintings of Maidu Indian artist Frank Day (1902-1976) describe Konkow Maidu ways, rituals and ceremonies, some of which he never saw or experienced. His scenes are based on memory, on stories, and where there is no specific memory, on imagination and improvisation. The paintings appeal in many ways. They are intense, vital and beautiful; and their content is significant to those involved in California native cultures. That explains why an anthropologist, Rebecca Dobkins, curated a 1997 show of Day's, aptly called Memory and Imagination: The Legacy of Maidu Indian Artist Frank Day, for the history department at the Oakland Museum of California.

"Memory is a subjective thing; all experience is," says Dobkins, who wrote her Ph.D. dissertation on Day. "Memory necessarily involves imagining the past, and so memory is not some kind of unfiltered truth or reality or object we can project outward. Without imagination, we would have no memory. We must use our creative modes of thought to construct from the past what gives meaning to our lives in the present. Even though Frank Day himself spoke of his work as if it was documentation--and he stressed that it was the truth and he could take you to it--what moves me is the incredibly creative spin he put on memory."

We know much more than we realize. As concentric rings record the life of a tree, humans keep the past alive unconsciously through gesture, habitual movement and thought patterns. The environment in which we live figures large in this chain of memory. If we live in an ancestral environment where prominent features of the landscape are virtually unchanged from generation to generation, we can intuit a lot about our ancestors' influences and experiences. Most of us do not live where our antecedents lived, but Frank Day did. His home environment was the northern California region around the middle fork of the Feather River, one of the most beautiful places on earth. The sentinel-like Big Bald Rock overlooks hilly forested country on one side and a breathtaking river canyon on the other. The swift, singing river in its bed of water-sculpted boulders, the fragrant vegetation and the sweeping vistas are unforgettable. Such a place resides in the heart of a people This still-remote, bountiful and regenerating place is Konkow Maidu country.

Day spent his early childhood in the Berry Creek area of this region with his father, Billy Day, and his grandmother (his mother died when he was two). He also spent eight years away from home in Indian boarding school. As a young man he traveled throughout the west, returning to his home territory in the 1930s. He took up painting after he was injured in a serious accident. His first subjects were non-Indian--a locomotive, a birth in a hospital--but before long he changed to Maidu themes and began to relate what he knew and imagined about the ceremonies, stories and experiences of his people.

With the construction of the Oroville Dam on the Feather River, great expanses of traditional Konkow country were scheduled to be flooded in the 1960s, and archaeologists and anthropologists were working intensively to document Maidu history and culture. So it is natural that Frank Day's first adherents were anthropologists such as Donald Jewell of American River College and his student Lyle Scott. Day's mission to share his culture perfectly coincided with theirs. He talked, wrote, tape-recorded memories and reflections, sang, taught dance; and painted. By 1973 his reputation as an artist had spread to dealer Herb Puffer, who wrote asking to handle his work at Pacific Western Traders in Folsom. Puffer played a supportive role for the last three years of Day's life, encouraging him, providing him with materials, and buying and showing his art.

Language is where we store our experiences and observations. It is the repository and indicator of culture, forming over time and closely related to the life of a people. Frank Day was translating the Maidu language into visual terms.

"Day believed that one's language shapes the way one views reality," Dobkins says. "He felt that Konkow Maidu speakers view the world differently than English speakers do, in part because of that language. The linguist Edward Sapir says we don't all live in the same world with just different labels attached. Frank believed that knowing the Konkow language was the route into the Konkow world view. Rather than translating into another language, English, and having to rely on imperfections of translation, he would do it visually. Showing a basket and its use, a roundhouse and its use, rather than telling about it in English, was for him an intermediate level of translation. It was not as good as knowing it in Konkow, but it was better than learning it in English, because it was coming from his own Konkow-based understanding."

Like many strong and imaginative individuals, Frank Day had a vision and pursued it. His father had been a headman, a leader respected by his contemporaries. Although more of a loner, Frank dedicated himself to communicating a culture, and his influence reached out to those who wished to share his vision--to young Indian artists and dancers.

"Often when we think of artistic influence we think of style issues, content issues, composition issues; that artists are responding to or working against some element of another's art," Dobkins says. "Frank Day has meant something more of a holistic influence. In other words, his example of affirming Maidu traditions, saying they are worthy of celebrating, worthy of artistic energy, gave younger people affirmation they needed."

When Day first started painting, self-representation for Native Californians was unusual. They were an almost invisible people. The 1960s and '70s saw emerging activism and efforts to raise public consciousness on issues such as Indian education. Speaking into his tape recorder in August, 1974, Day said, "One of the reasons why I'm doing this is to make these things clear, that one day it may be used for a good purpose. It's going to shoot all of your imaginations of what a California Indian is, because you don't know it. You don't know much about 'em, unless you are one. . . . The hardest part is how the suffering is, because you'd have to be born like one."

Artists Dal Castro, Harry Fonseca, and Judith Lowry felt inspired and empowered by Day's stories and paintings. Frank LaPena worked with Day to form the Maidu Dancers and Traditionalists, who make dance regalia, sing, drum and dance, carrying on the essence and spirit of their forebears. Herb Puffer and his wife, Peggy, provided space for their rehearsals and performances.

"Harry Fonseca always says that Frank Day was magic in more ways than one," Dobkins says. "It's to me the phrase that captures Day. He was mysterious; he was mystical; he was exasperating; he was magic in the good sense, and maybe in the more difficult sense. Any charismatic person is powerful and sort of overwhelming, and that is my feeling of Frank Day."

Frank Day's great accomplishment as a painter, she believes, is that over time his increasing creativity and skill went hand-in-hand with trying to communicate his Maidu world view. This view, while full of dignity, joy and beauty, doesn't flinch from death and suffering. Sorrow, loss and displacement are frequent and powerful themes, often represented poetically and symbolically. The Maiduans in his paintings live in another age of stability and harmony with the gathering place, the roundhouse, at the center. They hunt, fish, cook, care for their children and play games. They dance, engage in healing practices, mourn their loved ones, and die. Without preaching, Day leads us to his people's inner lives.

The Maidu world is also dangerous. Displacement is a frequent theme in this work--things rise, fall, are spit out, are grasped and then flung away. "As the Earth Trembles" shows the Maidu world in chaos. The roundhouse is in flames, a hot spring bubbles forth from a gash in the earth, children are left vulnerable as their mother, bound to a tree, watches, and their father is dragged to his death by a white horse, symbolizing the white man's treatment of the Indian.

Other paintings show conflicts that exist in nature: "Two Snakes Entwined", from about 1967, depicts enemies in a life and death struggle. "Two Eagles" presents a fierce air battle. "Mourning at Mineral Springs" illustrates a natural disaster, a sweet spring turned sulfurous by a tremendous earthquake. Day explained many of his paintings, and in this one he relates that the skeleton in the foreground is an old man who was trapped when the temblor occurred. The old man is mourned only by coyotes. The palette is somber, shadows are deep and dramatic, dark clouds advance. It is a poetic and sorrowful image.

Transformation is a constant theme in Day's work and spirits, humans and animals merge and interact. These transformations take place in creeks, falls, pools and rivers; hills, mountains, gullies; crevices, plains, rock formations, stones, trees, plants, flowers. Imprints of animals and humans mark the earth; the clouds, stars, sun, moon, sunsets and sunrises mark the passage of time. Earth, wind, water, fire: they're all in the paintings. Fire burns and destroys but also cooks and heals. Fire carries the spirit into the next world.

The paintings are full of motion and of opposites: a shaman rises, a hunter falls, a whirlwind spits out ill-doers.

In the glowing painting "Ishi at Iamin Mool," Day conjures up a meeting with the famous Yahi Indian in 1911, when Day was a boy, before Ishi turned up, hair shorn in mourning, in Oroville. In the painting Day surrounds Ishi and his companion, whom he is treating for a wound, with a healing circle of sun, water, tree and sky. The sun's rays reach out to the tools of healing--rope, a smooth stone--imparting continuity, power and love. This painting is important because it portrays Ishi as a man of healing power and dignity. He is not a frightened, emaciated survivor. This is the kind of memory that Day could summon. He binds what he recalls with imagination and the wisdom of a man of mature years who reflected deeply on the meaning of things.

"I think that he is, at these shining moments in the paintings, doing what he set out to do: translate the Konkow language, the Maidu world view," Dobkins says. "He doesn't do that in a strictly documentary way; it's these elements of imagination that richly and emotionally convey the sense of connectedness with earth, one another and animals."

Frank Day made 70 hours of tape recordings, some of them with an interviewer, many of them alone. He explained that he was talking for people in the future who would use his tapes to good purpose. At times during her study Dobkins believed he was talking to her, though they never met. He died when she was in high school.

She says she has always gravitated to older people. "I find their reflection on experience so important to understanding what life's all about without having to reinvent every square inch of it." Her mother, Betty, was an historian and a gifted storyteller. "She made my grandmother and maternal great-grandmother living presences in my life through her stories. She helped me understand that stories are what make us who we are. Stories about our family inform us about where we come from; stories of the past inform us about where we have gone as a people and society; and stories shape and enrich present experience."

She brought this belief to her study of Frank Day and learned the rewards of patience. "He spoke very much in a stream-of-consciousness manner," she says. "Very little of the recordings or writings are clearly organized or punctuated. They seemed rambling and confusing at first. But the more I listened, the more I understood that part of what was true for him was that everything had so much meaning, associations, layers of memory, that his way of expressing it was through digression, embroidering and coloring, in paintings and the language."

The exhibition, a collaboration with the museum's art department, marks the third time Day's work has been shown at the Oakland Museum of California. Day was included in the 1986 landmark show of folk and self-taught artists called Cat and a Ball on a Waterfall. "But this time," says museum Chief Curator of History Carey Caldwell, "there's a big difference. This is the most comprehensive examination of Frank Day's life and career ever undertaken. Further, in the process of Rebecca's research, and in our own work to further document our collections, we realized that our founding curator, Charles P. Wilcomb, had assembled a number of objects from the Berry Creek and Bald Rock area during Frank Day's childhood. One was collected in Billy Day's camp. Many of these are very rare objects of their type, and sometimes the only known examples in museum collections anywhere."

The objects, exhibited among Day's paintings, constitute an outreach to the Native California community. "We are seeking to create a situation where there can be more reunions between people and objects. A number of those who are direct descendants of those who made and used the objects Wilcomb collected are involved in our public programs," Caldwell says.

The placing together of Day's paintings with objects familiar to him, some used by people he knew, makes the exhibition very personal; and that brings us back to Rebecca Dobkins. In her years of research she came to know Frank Day well--as any biographer comes to know his or her subject--but eventually, academic interest was exceeded by her involvement with this remarkable man.

"Part of the process of doing biography is trying to get into someone's head or skin or self," she says. "What initially was very difficult was that his world and world view are so much a Konkow Maidu view, one not my own, and no amount of academic research could help me fully understand that world. His paintings in particular, but also his talk, have helped me think about that world. I feel he's inseparable from it. The more I've gotten to know him, his work, his words, the richer and more complex a human being he seems."

Art is a more direct medium than words, when the art is good. The immediate, visceral impressions one receives from Day's best work convince one that in painting he discovered the rhythm and heart of his message to the world.

Images from top:

- Cover of The Museum of California magazine, Spring 1997, with Frank Day's "Fish Dancer," ca. 1973-75, oil on plywood, 24 x 17 in. Collection of M. Leigh and Sandra W. Marymor. Photographed by M. Lee Fatherree.

Originally published in The Museum of California magazine.

No reproduction without express written permission of the Oakland Museum of California. This is a slightly altered version from the original, which was published in Spring 1997.