David Ireland: The Way Things Are (2003)

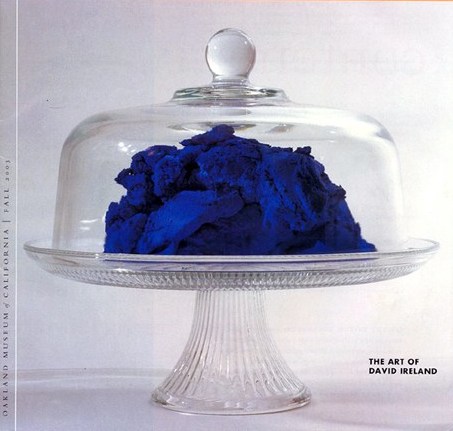

Cover of The Museum of California magazine with "Cake Dome Vitrine" by David Ireland, 2000-2001, glass cake stand and Fixall with pigment. Photographed by Anthony Cunha, 2003.

David Ireland: The Way Things Are (2003)

by Abby Wasserman

If a single work by David Ireland can puzzle, provoke and fascinate, what is the likely impact of a whole retrospective? With the opening of The Art of David Ireland: The Way Things Are on November 22, 2003, we are about to find out.

The single work I refer to is "Harp" (1991) in the Oakland Museum of California's permanent collection. It consists of an old stool, a white enamel basin such as one might find in a hospital, and a simple wire armature lifting a piece of cheesecloth that has soaked up yellow dye from the bowl. It is quite simple, but reactions to it are not. Some see it as a quirky demonstration of capillary action while some others are made queasy. It fits no standard criterion of beauty; it has no monetary value; it is not meticulously crafted. Yet it is undeniably powerful. I was drawn to it because of its oddness, because of the saffron light caught in the porous cheesecloth, the strangely juxtaposed surfaces and vulnerable wire armature.

Harp by David Ireland

"Harp" was my first introduction to Ireland's work and its enigmatic nature spurred my curiosity about the artist. When Senior Curator of Art Karen Tsujimoto told me she was organizing an Ireland retrospective, I couldn't wait to meet him. And so, in June of this year, I did.

Ireland is an almost legendary figure by now, although this is his first major retrospective, and the book the Oakland Museum has just published is the first in-depth assessment of his art (University of California Press, 2003). Tsujimoto, who has written previously about such diverse California artists as Wayne Thiebaud, Joan Brown and Peter Voulkos, regards Ireland as one of the most important artists currently working in the area of conceptual and installation art. For the exhibition she has chosen some 80 works made between 1972 and 2002, including four large-scale installations, 30 sculptures and 47 two-dimensional pieces. The work demonstrates the artist's adventuresome creativity. Ireland will be directly involved in the exhibition's installation. Tsujimoto anticipates a wide variety of visitor reactions to his work, and the museum's art docents will offer interpretive tours. She is eager to bring people into the circle of awareness. Ireland is difficult to categorize, but his work is gratifying once it is comprehended. It is Tsujimoto who arranges for me to visit Ireland at his San Francisco home.

David Ireland's 1886 Victorian in San Francisco's Mission District sits at the corner of Capp and 20th streets. A knee-high wrought iron fence borders the tiny front yard. The word 'ACCORDIONS,' in a first floor window, has been nearly rubbed away by time.

I look for a doorbell. I knock. Silence. I knock again. Through the glass door pane I can see a long, dark hallway and little else. Then I hear slow steps descend and after a moment David Ireland is at the door. His white hair and beard seem to float in the shadows. He has sky-blue eyes, a long nose, and slender hands with long fingers, and his skin appears almost translucent. He is dressed in navy blue and black. We mount the curved staircase with banisters of dark hand-carved wood. The second floor is flooded with sunlight.

There are sculptures, paintings and installations everywhere. The whole place appears to be a strange and wonderful stage setting. One doorless closet contains a sculpture resembling a cross between a meat grinder and a giant inverted clothespin. On the floor there's a pile of snow-white folded garments suggestive of hospital gowns. The hallway curves sinuously. The walls, burnished to high gloss, are hung with odd things: a chair, something resembling a dried cow patty.

The house is at turns elegant and homely, subtle and blunt, graceful and awkward, straightforward and enigmatic, playful and subdued. Many of the colors are somber: black, white, gray, brown; but the walls are the color of saffron Buddhist robes and there are vivid accents of institutional green, red, and Yves Klein blue, a vivid cobalt.

David Ireland is interested in architecture, sculpture, painting, stage design, drawing, and in homely objects and interior environments. The house showcases them all. Solidly built, it survived the 1906 earthquake. He is the third owner. He has stripped and uncovered what lay beneath layers of paint, moldings and floor boards, and refinished them so that the sun (there are no curtains) pours onto these shiny surfaces, making them shimmer. Years later he rehabilitated spaces at the Headlands Center for the Arts in Sausalito in much the same way, meticulously uncovering the beautiful bones that lay beneath layers of paint and grime.

We sit at a table in the front room. There's an eviscerated television near the fireplace and a ceiling fixture called "Flame Drawing" made up of suspended portable welding torches which, when lit and set into motion, draw in the air with flame. There are three large black oval objects, like oversized charcoal briquettes, just outside the fireplace, which is filled with white paper. There are also jars of dryer lint, rubber bands and hair.

Ireland is an Idea artist, a term he prefers to the more academic Conceptual artist, and he is a transformer of things. He looks places most of us don't look, uncovers things most of us never see, and saves stuff most of us would sooner throw out: used paper towels from his window-washing, for example, rubber bands he takes from newspapers, and sawdust from sanding the floors.

He places these things in jars, like historical relics. He documents the process of doing things. The unfinished look of windows without molding not only reveals how the window was set into the wall, but the kind of boards that were used. "I like to collect history, things that have been handled," he says. "I am interested in the residue of some type of action."

After buying the house in 1978 for his residence and studio, he intended to rid it of traces of the previous owner. He wanted to clean away the grime of years, the bathtub rings, the brooms worn down to nubs in every corner--to make it his own. But as he stripped, sanded and cleaned, he became interested in its structural bones and how he was contributing to its life story. He began to leave deliberate signs of what he was doing. He stripped wallpaper and squeezed the wet stuff so that after drying it held his fingers' imprints. He gathered the stubby brooms that had swept until they were worn away, and eventually made them into a sculpture.

The house was a rebirth and beginning. Through it he discovered a medium of distressed surfaces, found relics and social implements. He invited people in to see what he was doing. His house became a public happening.

"I wasn't trying to create a museum," he says, touching his fingers at the tips. "This was me--how one person lives. I sent out invitations and put notices in small newspapers. People would stay all day. It grew to where there would be 50 people in line. One afternoon 500 people came through. They couldn't see anything, it defeated the purpose. So I stopped doing it."

Ireland drew in a little. He isn't crazy to sell, though he does want to be recognized for what he is doing. He likes the flexibility of working on the house, of not having to finish things, put them out on view, and sell them to collectors. He treasures the idea of process, that he can keep working on things, letting them find their identities. "What you do is held in some privacy," he says. "Sometimes you're in an activity that becomes an artwork. It sneaks up on you. As you create something, you're a creator. There's a Zenness in it. You don't always know you're forming an artwork. You're bringing it to some kind of resolution. It's changing. It's loaded with metaphor and physical possibilities."

I ask about the Oakland Museum's piece, "Harp." Would he change it if he could? He muses, "You could bend the wire, resoak the cheesecloth. We can't be ruled by our viewers. Sometimes we have to destroy something as a way of expressing a deeper further thought in ourselves." The idea of the artist coming into the gallery to change a piece is a novel one--though if Joyce Carol Oates can make changes to a previously published book, why can't an artist adjust an artwork?

David Kenneth Ireland was born in Bellingham, Washington on August 25, 1930, the third of four children. He wasn't aware of a calling to be an artist, although when he was small his teachers put on his report, "David spends too much time looking out the window."

He enrolled in the California College of Arts and Crafts in 1951, studying nearly everything except sculpture. He graduated in 1953 with a B.A. in industrial design and a minor in printmaking, then served two years in the Army. Later he traveled to Europe and to South Africa, where he stayed on for a year and a half.

In 1958 he returned to Washington, joined his father's insurance company, married, and had two children, a son and daughter. He and his wife started a safari/import business called Hunter Africa, importing artifacts and big game skins. They moved to San Francisco, continuing their import business in North Beach, then expanded it to include photo and hunting safaris to East Africa. He climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro. Asked if Africa directly influences his art, he acknowledges that to an extent it does, but so does everything else he has done in his life. "You take things from the real world and mix yourself in. It can make the art richer and stronger. Africa is part of my resource bank." In one work he alludes to Africa and Van Gogh in one fell swoop. "Subtly reflected things are the most useful," he points out.

In 1972, after a divorce, he closed his businesses. He was 42 years old and had been away from art for 20 years. He entered the San Francisco Art Institute on the GI Bill. At the same time he took classes at Laney College in Oakland with Gerald Gooch. "The printmaking department was very good and David could experiment," Tsujimoto says. "He made art day and night." Among his works were monotypes that he would fold, bend and crumple, sometimes putting them through the press 50 or more times, layering the ink surfaces. "I was starting to think about process and materials, things that led eventually into the kind of work that interests me now," Ireland explains.

He will say that "you can't make art by making art," a statement that provokes questions about artistic intent and unpredictability. At what point in the process of making something does it become (or fail to become) art? Can a pragmatic task one is doing with cement or a sander or stripping gel suddenly turn a corner and become rich in ideas and evocative in appearance? Ireland's work suggests it can. And a finely rendered painting or crafted sculpture can fall flat for want of an original idea.

During the Art Institute years, Ireland once had his performance art classmates dress up like workers in the Financial District (three-piece suits for men, pumps and running shoes in a bag for women) and go down to the district to mingle for the day. Some didn't get back to the school until two a.m. He was creating a work that was invisible, so integrated into the world that no one could tell where the art stopped or started.

Eastern philosophies, particularly Zen Buddhism, have exerted influence on many West Coast artists and Ireland is no exception. In the 1960s he would stay up until the small hours of the morning to catch Alan Watts' radio program on KPFA. Watts would broadcast then because air time was at its most affordable. Ireland still has his copy of Watts' The Way of Zen (1957).

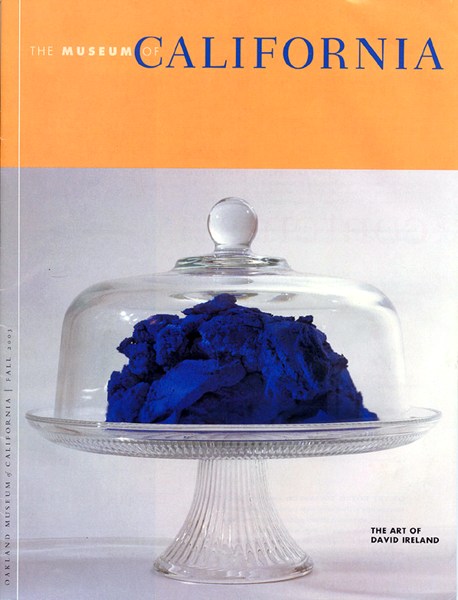

One of his signature works, the dumbball, a ball of cement made by hand, illustrates his Eastern approach to materials. "Anybody can make dumbballs," Tsujimoto explains. "All they require is concentration in the moment." Cement is ordinary, universal and cheap, and has no artistic pretensions. He likes its transformations, from a powder to a liquid to something rock-hard. One dons gloves and receives a wet blob of cement to pass back and forth between hands until it sets up, which may take up to 10 hours. The finished ball--dumb because it requires no intellect--is the size of the maker's hands.

Dumbball Action by David Ireland

In matters of color, too, Ireland eschews an arbitrary system of values. When he introduces saffron, bright red, Yves Klein blue or institutional green, their effect in the midst of neutral and "non-colors" is startling. The yellow, red and green he likes are also Van Gogh colors. His admiration for the Dutch artist is great. "Van Gogh can bring you to tears," he says. "He was a suffering man with no companions but his brother. I spent 1954 and 1955 chasing around Van Goghs in Europe. Some of his portraits! He would impose richness on his subjects. The whole shape of culture is dependent on people doing whatever it takes. It's not frivolous. The best work we know has agony in it."

Tsujimoto says she struggles at times to understand Ireland's work. "There are so many ways of looking at the world and David has helped to reinforce that. I've learned from him that art can be puzzling and doesn't necessarily have to soothe the eye or give an answer. I can say to him, 'David, I don't understand this,' and he says, 'Neither do I, and that's the beauty of it.' He is tweaking us out of our comfortable ways. He relates to the riddle of Zen koans. They too are baffling. David seeks to undermine logic, to provoke, initiate, to turn the mind inside out like a Zen koan."

The koan is often used by Zen practitioners as a subject for meditation on the path to awakening. A koan's effect lies not in the problem it poses (which makes no logical sense) but in the life of the practitioner. It would seem, by this definition, that creating the puzzle, engaging the enigma and accepting that one must live with uncertainty, are key to this effect, and are key also to understanding David Ireland's art. Like many northern California artists, he has been strongly influenced by Eastern philosophy. Karen Tsujimoto focuses on this influence and affinity in her essay for the book The Art of David Ireland: The Way of Things. "In Zen all things are equal and perfect as they are. It is folly to value one thing over another whether in art or life," she says. Ireland's interest in chance and process--in how something becomes and continues, perhaps circuitously, to find itself--fits well with this.

Ireland examines a piece of abalone shell I have brought. "There's so much to be looked at and contemplated," he remarks. "A lot of work I don't care for but I recognize its importance; it has value and merit. The fun part is asking how can I approach some idea? I want people to stop and look. Do I want to be understood by everyone or by an elite few? That's one of the breaking points where a person has to decide whether the ego is sufficiently in place. The possibilities of what we're asking the viewer to be aware of are endless."

I have brought a camera, and he invites me to go around the house snapping what I wish. There's a spider web across the bathroom window and it looks, against the white siding of the house next door and a cornflower blue sky, as if Ireland put it there. Being in his house makes me notice things more. I have expanded in his presence. "One of the beauties of art," Karen Tsujimoto has said, "is that it is constantly opening you up to new possibilities. I think that's what David's work does."

When I return to the front room he is sitting in a big leather easy chair, his hair back-lit like white flame. He asks if I want to see the basement before I go, and we descend to the shadowy, cool first floor. Upstairs the rooms are full of reflected light and objects behind glass. Downstairs there's a sense of ritual, tradition and history. Everywhere, things are stripped to essentials.

There's a long room with a huge table, cabinet and bureau that appears to be an altar to Marcel Duchamp. A framed photo of the Dada master is wrapped in bubble wrap. Is the bubble wrap a protective covering or an artistic statement? I feel sure that Duchamp would also approve of the magnificent horns of a cape buffalo and a gazelle set on the bureau, the fork set in cement in a sorbet glass, the pewter teapot painted half yellow, and the cement bow tie.

After a quick look at the kitchen--institutional green with industrial lighting--the visit is over. David Ireland says lightly, as he walks me to the door, "I'm doing what I do best, but I haven't figured out what that is." And it is likely, happily, to stay that way.

Images from top:

- Cover of The Museum of California magazine with "Cake Dome Vitrine" by David Ireland, 2000-2001, glass cake stand and Fixall with pigment. Photographed by Anthony Cunha, 2003.

- Harp by David Ireland, 1991. Metal basin, metal stool, wire, cheesecloth, fabric dye, C-clamp. Photographed by M. Lee Fatherree. Collection of the Oakland Museum of California Art Department.

- Dumbball Action by David Ireland, 1986, gelatin silver print.

© 2003-2005 Abby Wasserman. Originally published in The Museum of California magazine.