Coyote and the Myth-Maker (1987)

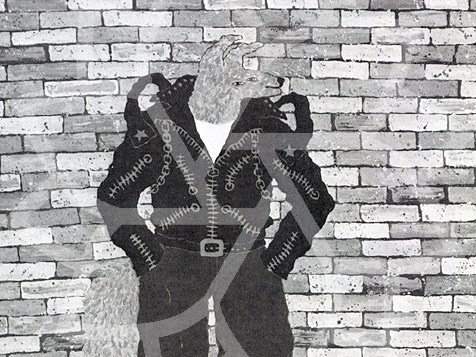

Coyote Leaves the Res by Harry Fonseca, 1982, oil on canvas. Courtesy of Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

Coyote and the Myth-Maker (1987)

by Abby Wasserman

If Coyote, the ancient trickster and changer of Native American mythology, were to walk into a room today, he might resemble Harry Fonseca, who is tall and slim with an alert, intelligent face and watchful eyes. Coyote is, after all, a spirit who can change form at will. In legend, he is variously described as an animal with tail and pointy snout, and a man--old and ugly or young and handsome.

Coyote is a magical figure who can bridge worlds and transcend time. He is the most powerful, yet the most "human" of the Native American gods and demigods. Virtuous and deceitful, mortal and immortal, ordinary and extraordinary, Coyote personifies deeply conflicting impulses. He is a symbol of survival, adaptability and balance.

Harry Fonseca has been making images of Coyote for more than a decade. His earliest drawings were dancers in traditional regalia and coyote headdress, the "spirit impersonators" of Maidu ritual. Then he catapulted Coyote into contemporary times to fashion a modern myth of Coyote in the city. The images are full of humor, yet speak directly to the challenges of our time. Ever-resourceful, ever alert, Fonseca's Coyote leaves the reservation. He hangs out in the city in a black, metal-studded leather jacket and high-tops. He poses as a tobacco store Indian in full eagle headdress and Levi's outside a Hollywood studio. With his female coyote counterpart, Rose, he dances a pas de deux from Swan Lake, or sells pottery, jewelry and kachina figures at Indian Market.

"Using stereotypical images of Indians, and making them vulnerable through humor, Fonseca challenges the viewer," says Margaret Archuleta of the Heard Museum. (Archuleta's exhibition of Fonseca's work, Coyote: The Making of a Myth, came to the Oakland Museum of California in 1987.)

Many of today's Native American artists blend contemporary media and methods with age-old Indian themes and symbols. Transformation and transmogrification are frequent themes. The animals they sometimes use as subject matter are not the animals of Aesop's fables and children's stories; Coyote tales are not "only stories" or even symbolic tales, but sacred explanations of origins and events.

Ella E. Clark wrote in her anthology Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest, "The animal people in the myths [were giants] . . . [with] the characteristics of today's animals, yet they could reason and talk and do many things that neither animals nor people can do now. The animal people in the tribal tales lived exactly as the Indians themselves lived later. They fished and hunted, dug roots and cooked them, lived in lodges, used the sweat lodge, had headmen or chiefs. . . .

"At the end of this mythical period of the animal people, 'the world turned over,' 'the world turned inside out,' or 'the world changed,' often quite suddenly. Human beings were created; the animals shrank to their present size, some tribes believed, and became more numerous. . . ."

Lowell John Bean, curator of North American ethnology at California State University, Hayward, writes of Fonseca's work, "By continuing to employ the iconographic symbols of the past, such as coyote, bear, deer and eagle, today's artist underlines the fact that these animals have since time immemorial survived magically as well as biologically. They tell the people that despite tragedy the strength of the traditional culture is such that it will survive, no matter what exigencies of historical circumstances descend upon it. . . . [Harry Fonseca's] use of Coyote as a symbol gives contemporary persons a sense of history and place."

Many tribal myths refer to Coyote as the Creator of the first human beings. According to the Maidu tradition, Archuleta writes, he is also responsible for the existence of work, suffering and death.

The dichotomy of Coyote as creator and destroyer lies at the heart of Maidu mythology. "In many cases Coyote reminds me of a human psyche, or humans in general," Fonseca says. "Like him, we are capable of such creativity and such destruction. Coyote is a survivor and a trickster . . . but in some cases, he is also a 'stripper.' He can give you the world and strip you of many things at the same time."

Adds Archuleta: "Coyote is bigger than life and encompasses so much, that no matter what your cultural background is, there is something there that the coyote imagery can be related to. Humor is the key to his universality."

Coyote survives because of his adaptability, but there is always a risk to change. Fonseca says, "You gain and lose something. You have to weigh those gains and losses, and make changes with awareness and clarity. Coyote just responds. He doesn't take time to reflect. As human beings, we also respond too quickly to things."

Besides teaching "how to get through situations, what to be aware of, and how to increase our awareness," Fonseca says, Coyote also teaches us to have a good time. "That's what I understand about my coyotes. They are yin-yang, black-white, negative-positive. After awhile there's no separation; the shades of gray come. My coyotes are always gray. I have tried to make them brown, but they come out gray. Actually, coyotes are many colors--usually like a tattered old coat. Coyote is a hard figure to pinpoint. He's in flux constantly."

Rose on Point by Harry Fonseca

Harry Fonseca was born in 1946 in Sacramento, where he lives once more with his wife and daughter. He is of Maidu, Portuguese and Hawaiian descent. An artist by inclination from a young age, he was greatly influenced in his Maidu consciousness by his uncle Henry Azbill, a Konkow Maidu elder who was a tireless promoter and preserver of Maidu culture, which had been decimated after gold seekers and settlers invaded ancestral lands in the northern Sierra Nevada.

"The beginnings were my artwork and becoming aware of being Maidu, that it was more important than just being Maidu," Fonseca said. "I became aware of the potential. There was a whole life I had jumped over, and now I picked it up."

The first time he saw the Coyote Dance, he was struck with how much fun the dancer was having. "He was such a kick, and I thought this is really wonderful--to have a religious approach to life and a little levity, a little escape. You have strength in both of them." Gradually and quite naturally, images of Coyote began to dominate his work.

While a fine arts student at Cal State/Sacramento, Fonseca tape-recorded his uncle telling the Maidu creation myth. In 1976, he applied for and received a special projects grant from the California Arts Council to paint "Creation Story," which he had come to understand was the history of the Maidu people. During this period he was initiated as a dancer. He spoke with elders and collected photographs. With others, including artist Frank La Pena, he founded the Maidu Heritage Foundation "so that all of us can bring these pieces together that are many puzzles."

Fonseca initially had no idea that he was making a myth of his own. He saw a television program in which Bill Moyers interviewed Joseph Campbell, and experienced a shock of recognition. "I thought Campbell was talking about me," Fonseca recalls. "He said that Romeo and Juliet are alive on a street corner in New York, and that's true. In so many ways, mythology is connected with life. It comes from life. If these experiences and thoughts hadn't occurred in people, we wouldn't have these myths.

"Campbell said you could tell the importance of a myth in a place by the buildings. In medieval Europe, everything in the town was built around the cathedral. Today, the largest buildings are banks and corporations. Everything revolves around economics. We're not looking for the Golden Fleece anymore, but you are looking for the big client.

"Not all myths survive. Some slip away. And mythology doesn't give you many answers. The Christian religion has been able to take many events over time and put them in order and by category to formulate a right and wrong. With Coyote, order is pushed aside. All the information is there, but it's up to you to figure out how to use it."

Fonseca remains true to Coyote while extending his adventures into the present. Rose, Coyote's companion, is an invention of Fonseca's. The coyote of ancient legend has wives who often died tragically (or ran out on him), and many sexual partners, willing and unwilling. Rose is a Ms. Coyote, an equal. Fonseca created her the same night he painted "Coyote Leaves the Res" (1982), in many ways the seminal work of Coyote's urban peregrinations. After that, his male and female coyote figures developed together.

"In order to make a myth live, or to use that myth, it's got to change," Fonseca said. "I think that Rose has really helped to do that by opening up a whole new area of gender, where women on the 'res' really identify with this husky figure. There's a myth there, but she certainly isn't the Virgin Mary."

Translating the multidimensional oral storytelling experience to two dimensions is a challenge Harry Fonseca has met by adding what he terms "rumble" to his paintings.

"When I first started working with the coyotes, I was conscious of the 'coyote vision,'" he said. "I thought if Coyote was going to buy a painting, what kind would he buy? I realized he'd buy two kinds: one a very sappy reproduction of a landscape at Woolworth's in a little gold frame. Or he'd buy something really sparkly. The bright, circus approach to the work comes from that. I use thick paint, glitter, velvet. Those materials give the paintings a certain rumble. They don't just sit there. They demand your attention."

He's willing to extend his modern Coyote myth as long as there are places for Coyote to go and things for him to see, and that could take forever. "I don't think the Coyote mythology will ever dry up," he said. "It's been around so long. It opens like a Pandora's box. I think I could keep it alive; it's that potent. I don't know if I want to, however. There's something about the Coyote mythology that is so appealing that you don't see other things at times, and there are other things that are important and delightful. But this darn Coyote goes everywhere."

He adds reflectively, "He reminds me of those multi-faceted crystal balls hanging in the window. You see flashes, but you don't know where they will take off to. I'm trying to get to that core in my work."

Images from top:

- Coyote Leaves the Res by Harry Fonseca, 1982, oil on canvas. Courtesy of Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

- Rose on Point by Harry Fonseca, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History.

Originally published in The Museum of California magazine.

No reproduction without express written permission of the Oakland Museum of California.